There’s a small place that plays an important role in A Dark Steel Death. Gipton Well, or Gipton Spa Bath House or Gipton Well and Waddington Bath, to offer the full titles, has its part in the book, although I’m not about to give you any spoilers on exactly what.

It’s one of about 26 wells or spas that once existed around Leeds (including the wonderfully-named Slavering Baby Well in Adel), but are mostly covered over or long forgotten, except in some local names, like Sugarwell in Meanwood).

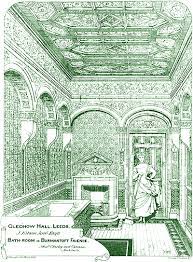

It was originally built in 1671 by Edward Waddington. His grandfather, Alderman John Thwaites, owned Gledhow Hall, and the well was in the estate; on private property, in other words.

Like so many spas, the water which entered the bath house supposedly had healing properties supposedly head healing properties. Leeds historian Ralph Thoresby brought his son Richard there, attempting to cure him of rheumatism, and that involved sitting in the stone-built cold water bath. Lord Irwin was also a regular visitor.

Next to it was a room with a fire for undressing and warming up after a dip in the plunge pool, with a separate spring with water that could be drunk.

Thoresby referred to the place in his Ducatus Leodiensis, where he states the room with its fire is used “to sweat the patient after bathing”.

Edward Parsons also commended the place in his History of Leeds in 1834, and as late as 1881, Kelly’s Directory noted it was still in use, although now it’s “by people who live in the neighbourhood.”

Shortly after it had fallen into disuse and disrepair, to the extent that when the Honourable Hilda Kitson bought Well House Farm (again, the association with the well), which included the spa, she offered £200 to the Council to keep up the spa. The city bought the spa and the land around it in 1926, just after Gledhow Valley Road had opened a few yards away.

While the building has been there for a long, long time, no one seems sure when the walls around the pool were built; certainly much later. I’ve included them in the book purely for plot reasons.

The Friends of Gledhow Valley Woods (an excellent organisation who also provided much of the historical information from their website. Take a look at it here) have doner a great deal of work on the place, and now it’s surrounded by a metal fence to stop vandalism. However, it was open on Sunday as part of Heritage Open Days, and I was able to go inside and take some photos.

Tom Harper’s spectre didn’t fill the place. But after seeing the pictures you’ll be able to be there with him. And I’m sure you will read the book. Hopefully buy it, too, to make sure the final one in the series in published. Thank you.