First of all, a happy 2025. May it bring you healthy and happiness and a sense of calm.

But…new year, new series?

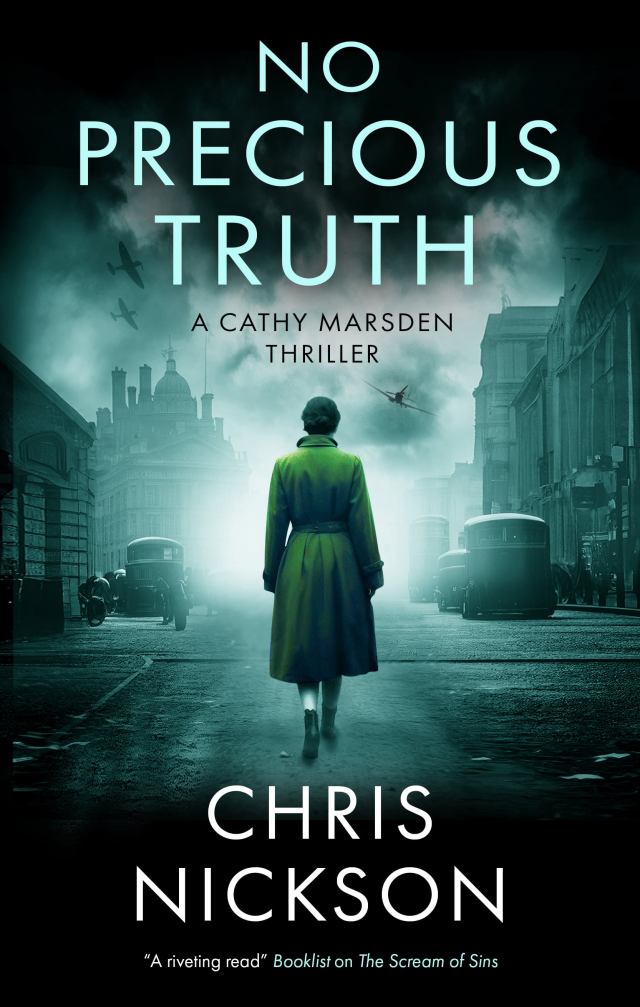

It’s true, I’ve dropped hints and more on here about it. With No Precious Truth (out April 1) I’m shifting to the Second World War and Leeds in 1941.

To begin, I should say I wrote an entire unpublished novel with Cathy that detailed her start with the Special Investigation Branch. And I discovered that she, the era and the situation would not leave me alone. She demanded I write more. The last time that happened was with Annabelle Harper, so draw your own conclusions.

Cathy Marsden was born and raised in Leeds, growing up on Quarry Hill until the family was rehoused to the brand-new Gipton estate in 1934. The city and its people is in her blood – more than she realises at first. Her father receives a pension, lungs ruined by mustard gas at Arras in World War 1. Cathy is a policewoman, a sergeant. She’d been in charge of six female police constables and reporting to a female inspector – at least until September 1940, when she was seconded to the Special Investigation Branch, which had opened a small Leeds office in the summer. The idea was she’d show the five men in the squad around the city. The SIB was made up of former police detectives who’d joined the army or been in the reserve, only to end up in the military police, and then SIB. They have army ranks, are supposed to carry sidearms, and work out of a small office in the Ministry of Works office on Briggate.

Where was that? Does this look familiar?

Now take a look at this. It was supposed to be the flagship Marks & Spencer store, but it was requisition by the government for the ministry.

Entrance right here.

The secondment was meant to last three weeks. In that time Cathy proved to be vital to the squad. Working in plain clothes, with her local knowledge, her skills have chance to blossom and the period is extended until she’s there for the duration.

But there’s one other thing she does. Every Friday evening, from 6-10, she’s a firewatcher at the top of Matthias Robinson’s department store, just up Briggate (it became Debenhams, and just reopened as Flannels).

There have been air raids, but Leeds has escaped the horrors inflicted on other British cities – so far. But how long can that last?

Meanwhile, Cathy and the men in SIB are going to have a very big problem. The first inkling is the return of her brother, who moved to London as soon as he could and is, he’s told the family, a civil servant…well, read for yourselves.

From the corner of her eye, Cathy caught sight of someone else entering the room. Her eyes widened in disbelief. He wasn’t anyone she’d ever expected to see in this place. She folded her arms and glared at him.

‘What the hell are you doing here?

Daniel Marsden was five years older than her, the clever boy who won the scholarship to grammar school. The one who passed everything without seeming to do a stroke of work while she studied deep into the night, struggling with her lessons and failing half her exams.

He was the boy people noticed. They remembered him, asked after him, always full of praise, with Cathy a poor second. When Dan landed a Civil Service job and moved down to London, she’d said nothing, but deep inside she’d been glad to see the back of him. After so many years she had the chance to move out of her brother’s shadow. Even now, his Christmas visits each year felt like more than enough time together, watching everyone gather round him. She’d been quietly relieved when he’d said there was too much going on at the ministry last December to be able to come.

Now he was standing in the office where she worked. He smiled.

‘I like the way you’ve had your hair done. It suits you.’

Cathy felt herself bristle. At twenty-six, she’d spent four years as a woman police constable, then two more as a sergeant, before her secondment to SIB and a move into plain clothes. She’d had to fight for respect every step of the way. It had been the same when she started here. She’d needed to work hard to make the squad accept her. To understand that a woman could do this job. Cathy wasn’t going to let her brother dismiss all that with a flippant comment. Just the sight of him here, where she’d built a place for herself, made the excitement and pride at finding Dobson wither away.

‘I’m so very glad you approve.’

Dan shifted his glance away.

‘He’s been sent,’ Faulkner told her. ‘We’re working with him.’

She turned, fire in her eyes. Like the other men in SIB, Adam Faulkner had been a police detective before the war. He’d been in London, a member of the Flying Squad. They were famous, the best Scotland Yard had; everybody in the country had heard of them. He’d joined the army, eager to defend his country, only to find himself shuffled into the military police. Recruited for the Special Investigation Branch when it was formed the year before, last July he’d been posted to Leeds to set up this new squad. A sergeant, like her, but his was an army rank. A good, fair boss.

‘Sent?’ Cathy asked. ‘What do you mean, sent?’

Faulkner closed his eyes for a second. ‘Your brother is with the Security Service,’ he said.

I hope you’re intrigued by a female character front and centre in a Leeds WWII thriller. If you’re registered there with my publisher, No Precious Truth will soon be available to read on NetGalley, in exchange for an honest review. If you’re not registered and fancy it, drop me a line and I’ll arrange it.

Or you could pre-order it, of course. Amazon has the Kindle edition of No Precious Truth pretty cheap in the UK and US. UK version here. In the UK, the cheapest hardback price is here. The cover’s pretty great, too.

And of course, the Kindle version of the latest Simon Westow book, Them Without Pain, is pretty decently priced in the UK. Find it here. The hardback is just over a tenner, too.

One final thing: Cathy arrives with her own soundtrack. Find the playlist here, but be prepared to dance and jitterbug.