The North of England was home to many religious dissenters and sects, those who worshipped outside the established religions. Preachers toured, held revivals, spoke to whoever might listen and tried to covert others. Most of those doing the talking were men.

Ann Carr was very much an exception. In Leeds, as well as preach, she did a great deal to help the poor, to educate their children, and take them in. She lived and died among them. Her deeds matched her words.

She didn’t do it for fame or glory. She did it as a part of her religion, her belief. Charity truly did begin at home. Yet who in Leeds has heard of Ann Carr? She deserves better than that.

The Shaping of Faith

Ann Carr was born in Market Rasen, Lincolnshire, the youngest of 12 children. Her father, Thomas, was a builder. Her mother, Rebecca, died when Ann was five, and she was raised by an aunt who became the family’s housekeeper.

When she was 18, the men she intended died suddenly, and Ann experienced what we’d call a breakdown for the three months. Finally, she attended a pray meeting, where ‘an aged Christian female came to her and said, “Ann, my dear, believe.”’

She did, and her life was changed. She became a Wesleyan Methodist, moving to the spontaneity of Primitive Methodism as she began travelling to preach to miners in Nottinghamshire. From there, she and two other female preachers, Sarah Eland and Martha Williams, were sent to Hull, where they opened the first Primitive Methodist chapel, and then on to Leeds in 1821, supposedly to support the work of preacher William Clowes. Ann had found the place that would be her home for the rest of her life.

In Leeds

The women made their home at Spitalfields, on the Bank (Richmond Hill as it is today), one of the poorest areas in Leeds. By 1822, however, chafing at the discipline imposed on them by the leadership of the church, Ann broke away and founded the Female Revivalist Society – the first religious revival society led by women.

Their home wasn’t big enough for their meetings, so Ann rented a much larger room in George’s Court, off George Street – ironically, where the upscale Victoria Gate shopping centre now stands. She (along with Martha Williams) lived there, they and began their social work among local people. It was a time when industrialisation was taking hold and people who’d been displaced by the Enclosure Acts in the countryside were pouring into town to seek work in the new manufactories. Leeds has no shortage of the desperate and destitute, and the Female Revivalist Society helped them.

By 1825, they’d moved to the Leylands, to Regent Street, where Ann had purchased land. On March 7 the first stone of Chapel House was laid. Ann would have that as her home and base for the remainder of her life. She, and her movement, were popular among the working-classes. She didn’t condescend to them. She was a part of them. In 1826, she expanded south of the river, with a chapel in Brewery Field. Holbeck, and a year later she opened a schoolroom on Jack Lane in Hunslet, as well as societies in Morley and Stanningley.

All of this took money. Neither Carr nor Williams came from wealthy family. They had to raise funds to keep going.

“Little did she imagine the fearful responsibility she was incurring and the trying difficulties in which she was involving herself,” Williams wrote in her Memoir of Ann Carr. “The tendency of these engagements was to secularize her mind, to paralyse her exertions, and to impair her usefulness. Much precious time…was…spent in going house to house , to solicit donations and subscriptions on behalf of these buildings, for the whole of which she alone was responsible.”

A total of £3339 was spent on buildings in Leeds, and preparing the deeds. Not long before Ann died, she still owed £2105 – almost £250,000 in today’s terms.

As well as trying to look after the poor, once she’d settled in Leeds, Ann brought her elderly father from Market Rasen to lived with her. Try as she might, though, she couldn’t covert him. Yet, in a scene that could almost be maudlin, he finally relented on his death bed.

Even with pressing money worries, Ann still managed plenty of preaching. She travelled outside Leeds quite often, and trained her horse to stop whenever it saw a group of men working, so she could preach and try to convert them.

Ann herself was described as “robust-looking, bold, courageous, and energetic, her preaching being characterized by zeal, correctness, and sincerity rather than by eloquence and culture.”

During the 1830s, with the rise of the Temperance Movement, saw Ann going further – back to work in Hull and as far as London. But she always returned to Leeds, helping the poor, educating children, and housing kids, prostitutes, those who didn’t have a home, at Chapel House.

When cholera raged in Leeds in 1832, according to the Memoir, “she refused no application, however desperate the case or unseasonable the hour. Often, in the stillness of midnight, the knock at her door has disturbed her sleep; when she has instantly arose, as quickly as possible dressed herself, flew to the house of contagion or death, pleased for the sufferer in all the agony of prayer, and urged him to apply to the skill and tenderness of the great Physician.”

In 1838, she and Martha Williams published a book of hymns. Whether it helped them raise much money to cover their debts isn’t known.

By 1839, Ann’s own strength was beginning to flag. A change of air was advised, and she left to spend time by the sea in Cleethorpes, then on to Market Rasen. The following year, her finances must have been precarious, as other denominations held a bazaar at Belgrave Chapel to raise funds for the Leylands Chapel.

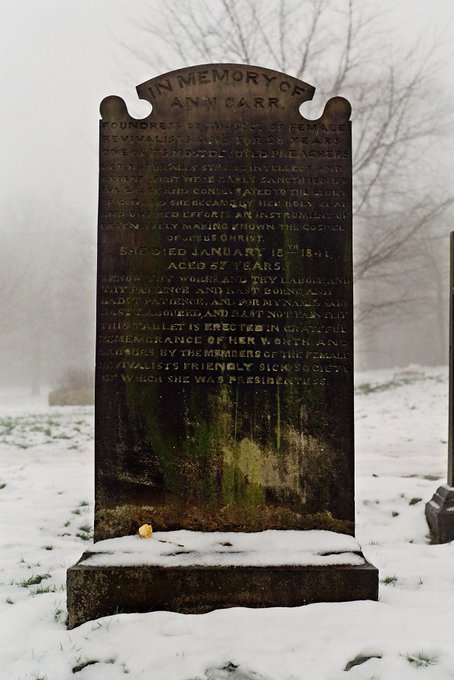

That autumn, with a change of air again advised, she spent four weeks in Nottingham, but it didn’t help. At this stage, nothing could. There was no treatment for the cancer in Ann Carr’s body. She died at Chapel House on January 18, 1841 and was buried at Woodhouse cemetery on January 21. According to Martha Williams, “thousands assembled” to watch the funeral procession pass.

The Leeds Mercury gave her a reverent obituary, and the Leeds times wrote that “she was a person of the most benevolent habits and philanthropic disposition.”

Martha Williams was named as her executrix, and working with trustees attempted to pay the amounts owing on the properties. However, Ann had left instructions to sell some of the buildings if necessary, “so that the Leylands Chapel should be carried on, and perpetuated for the purpose for which it was erected.”

Sadly, without Ann, the money didn’t come in, and the followers drifted away. Within a few years all she’d built was history. The chapel became the Temperance Union and then St Bridget’s Roman Catholic church. It’s no longer standing.

However, apart from heading possibly the first female-run religious movement, Ann Carr also helped some of the poorest in Leeds with their everyday lives – and deaths. She did the very practical things of helping to feed them, house them, educate them. It was a duty to her, but more than that, part of her vocation as a preacher. She made a difference here.

You can read and download the Martha Williams Memoir free (and legally) here.

My thanks to Morticia for her enthusiasm for Ann Carr.

Jst a final note. My new book, Brass Lives, is out in harback in the UK. It’s available everywhere on ebook from August 1, and hardback in the US from early September. I’d love it if you bought a copy.