It’s been several years since we went up to Richmond. Well before the pandemic, in fact. It’s a glorious market town in North Yorkshire with a spacious market square and a fabulous Norman castle, a perfectly picturesque place

After so long, it was definitely time to go again. But first, a detour. Someone had told my partner about Easby Abbey, fairly close to Richmond – you can walk there along the river in about 40 minutes. I’d never heard of the place, but a quick search showed it, with the ancient church of St. Agatha alongside. Everything free.

Pulled into the car park and had a quick chat with the man who’d been picking rubbish.

‘I’ll open it up for you,’ he said, and unlocked the church.

Stepping inside was a revelation. The earliest part dates from not long after William the Conqueror invaded, and the font is also Norman, as are the stone benches by it – the only early seating in churches.

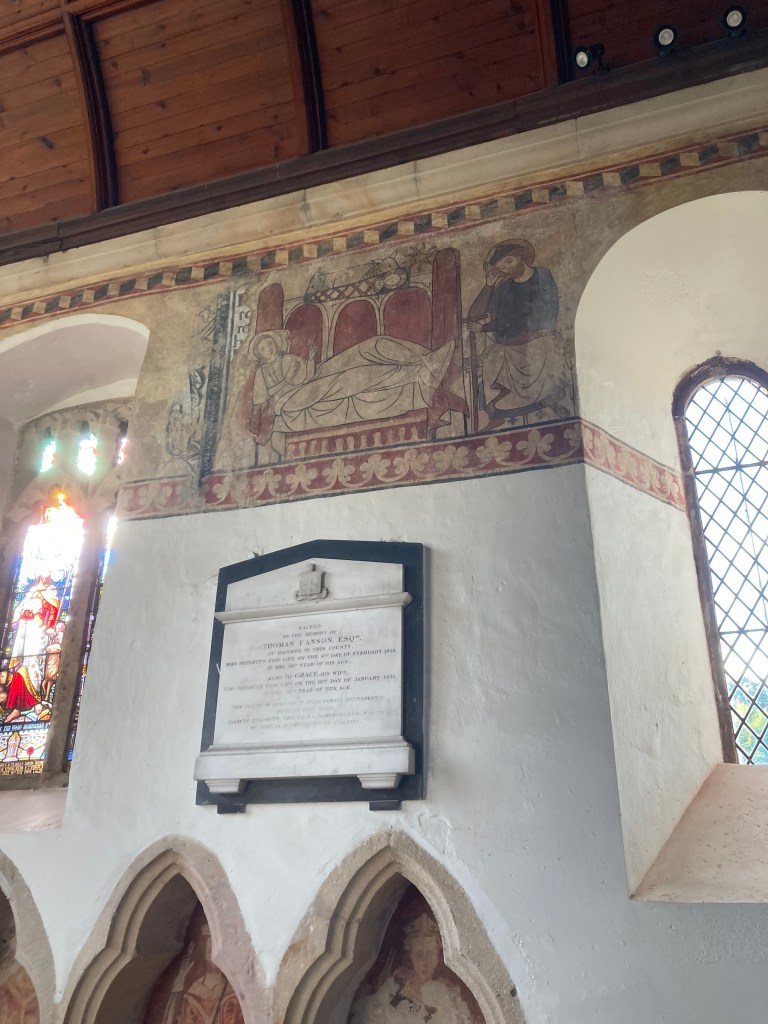

But the true glory is in the medieval wall paintings. They’d been covered over, probably to protect them during the Reformation or Civil War, to be uncovered in Victorian times and restored in the 1990s.

It’s estimated that the paintings date from around 1250 CE and tell different stories from the Bible. In those times, few could read, and the number that could read Latin – the only language in which the Bible was available here – was smaller still. Not even all priests would have been fully literate. Think of these paintings as holy comics or cartoons to tell the stories to the congregation.

It also boasts a (not especially great) replica of the Easby Cross. The original was found in the walls during work almost a century ago and sold to the V&A Museum in London. However, the design is quite something, as is the age, going back to the late 700s, making it an excellent example of a Saxon cross and probably from the first church on the site.

The church, restored a few times, is in a remarkably fine state; it really does take the breath away. After all, this isn’t even a church in a market town. It’s in an isolated hamlet. The name Easby derives from the Norse name Esi and the suffix by, meaning farm. At the time it was built, the entire parish held perhaps a hundred people.

It stands cheek and jowl by the ruins of Easby Abbey, which was built almost a century after the Norman part of the St. Agatha’s church. The abbey was a regional home to the Premonstratensian Order of regular canons, more widely known as the White Canons for the colour of their habits. They would have served as priests at St. Agatha’s and other churches all across the lands donated to them, and often distributed food where it was needed. They weren’t monks – their services was outside the abbey, not a contemplative life within the walls.

Even so, it’s a large place, one that lasted until the Dissolution in 1536, when those still there were granted pensions and sent on their way. The abbey slowly crumbled after that, and local would have taken stone for their own building projects. Yet even in the ruins there’s a sense of history; you can almost hear the voices of the canons.

What about Richmond? Great to see again, of course. It’s hardly changed, which is perhaps good. But the day was easily dominated by Easby.

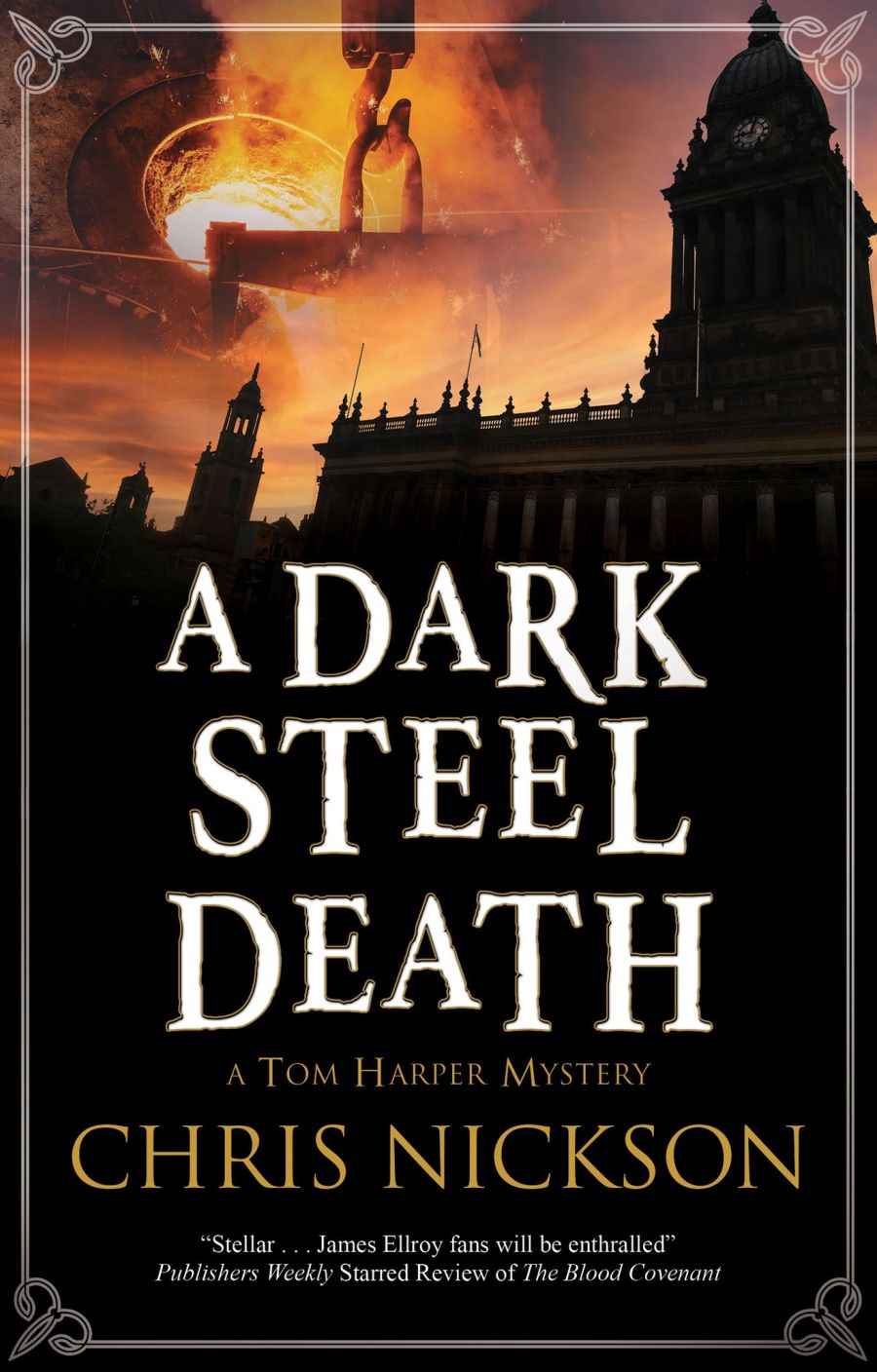

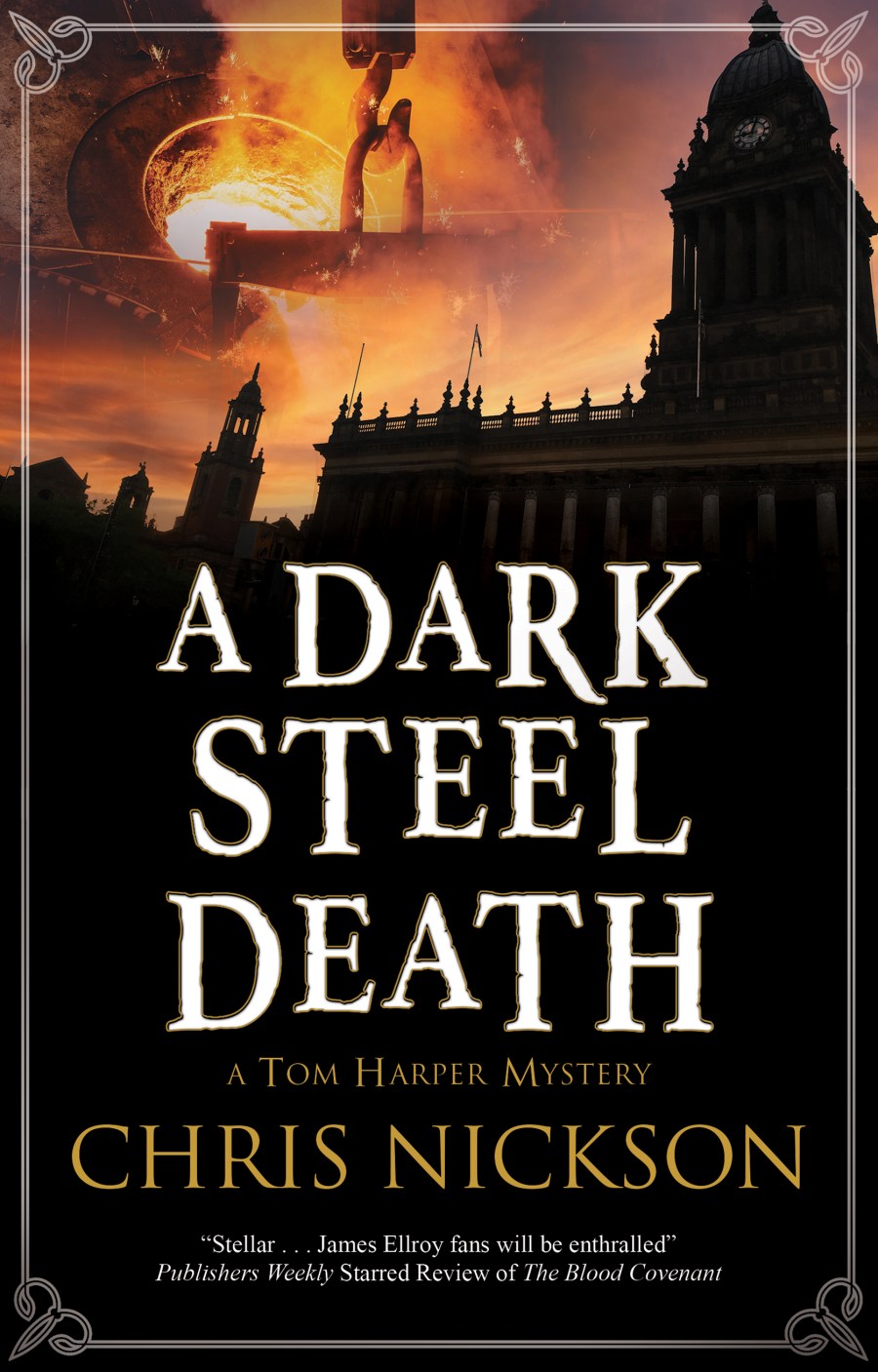

Yes, a lovely detour to medieval times. But, please, I hope you’ll remember that A Dark Steel Death is now out.