It’s just over a week until Christmas 2025, and the spirit moved me to write a new Annabelle Harper Christmas story. Yes, it’s unashamedly sentimental, but this is the time of year for that. I hope you like seeing Annabelle again, and enjoy her outing.

Leeds, December 1905

‘Give over,’ Annabelle Harper said. ‘The brewery knows better than that.’

‘That’s what the drayman told me when he delivered the beer this morning,’ Dan the barman told her. ‘Swore up and down it was gospel. They’ve got some kind of problem, so they’ll be limited in how many barrels they can let us have between now and early January.’

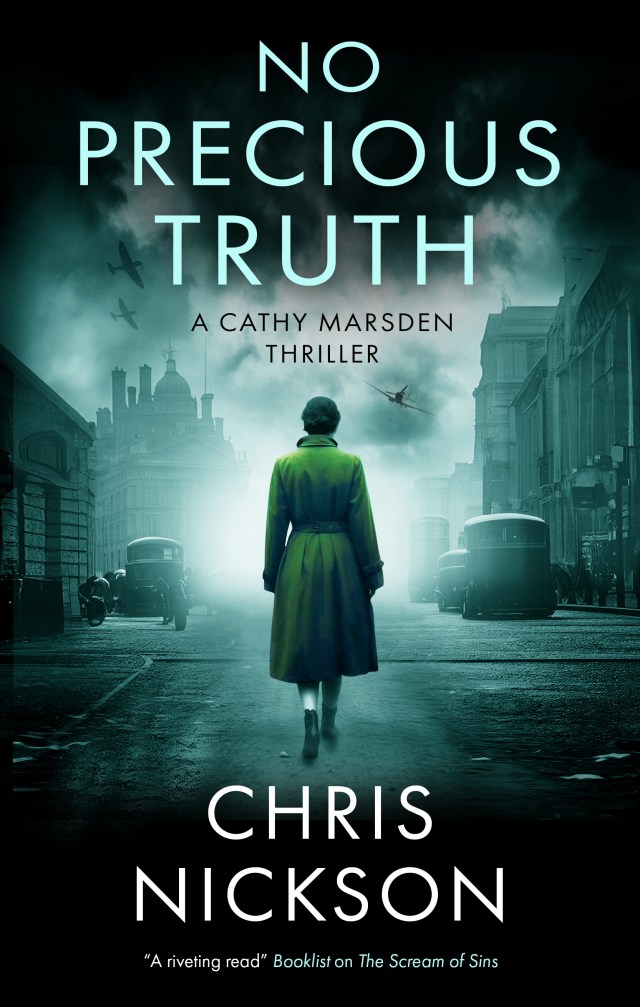

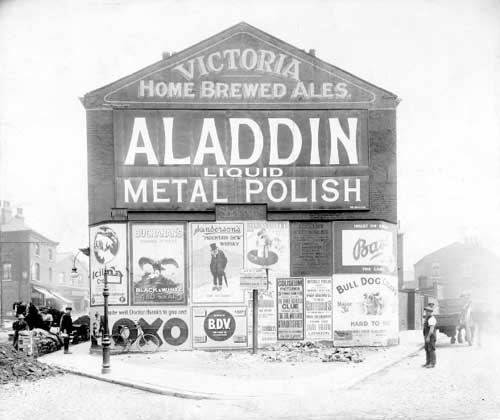

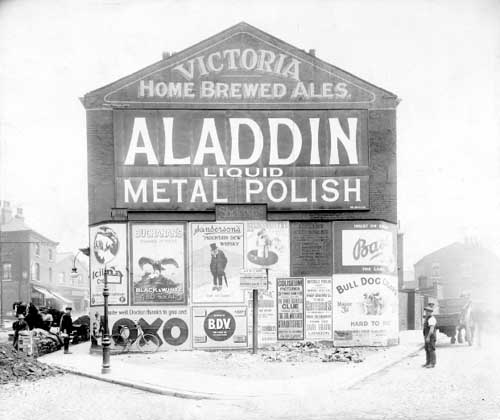

‘Right,’ she replied. Right.’ Her face was set. She ran the Victoria public house at the bottom of Roundhay Road. To be told just a week before Christmas that she wouldn’t have her proper order when the place was going to be full every night was the last thing she needed.

A glance through the window showed the rain outside was easing. At least that was something; she wouldn’t end up soaked on her way to the brewery. Skirt just short enough not to brush against the pavement. A coat, hat, sturdy button boots and an umbrella and she set of down Sheepscar Street to the brewery. It wasn’t far, just enough distance to work up a temper. Annabelle was a good customer, sold a lot of their beer and expected better treatment, especially at this time of year.

She was so wrapped up, planning what she was going to say, she almost passed the woman hunched in the doorway with a baby against her chest and another little one huddled against her.

‘Can you spare a penny or two, please, missus?’ She had a cracked voice, pleading, face chapped red by the chill in the air.

Annabelle squatted by her; a single glance was enough to tell her everything.

‘How long have you been sleeping out here?’

‘Last night was the second night.’ The woman turned her head away as if she was ashamed.

‘What happened?’

‘Me husband took off with his fancy piece,’ she replied in a mix of sorrow and anger. ‘Without his wage, I couldn’t pay the rent.’ A helpless shrug. ‘The landlord put us.’

Those children needed to be indoors, somewhere away from the cold. Warmer clothes, too, and some hot food in their bellies. The woman…she was downtrodden, as if all her hope had fled with he husband.

‘Do you have any family?’

‘No, missus, not any more. My mam and dad died, and me brother went off with the army and got hisself killed by the Boers down in South Africa. A penny of two would help if you can spare it, missus. I can get them something.’

The young girl at the woman’s side was silent, wide eyes staring up at her. Annabelle knew she could send them up to the workhouse. She was a Poor Law Guardian; they’d find a place on her say-so. But she knew what would happen. The girl would be separated from her mother. No, that wasn’t the solution.

She dug into her bag and took out a notebook and pencil to write a few lines. She ripped out the page and put it in the woman’s icy fingers.

‘Do you know North Street?’ It was close, no more than five minutes’ walk away.

‘Yes, missus. Course’ Her eyes narrowed, suddenly suspicious. ‘Why?’

‘You go to the address on there and talk to Mrs Wainwright. She’ll fix the three of you up with a room. Full board, too.’

‘But I don’t have any money.’

‘All taken care of for the next three months,’ Annabelle told her with a smile. She produced two one-pound notes. ‘Take those and get some clothes for the kiddies. For youself, too, you must be perished.’

‘I can’t-’ she protested.

‘Yes, you can. You’d have taken a couple of pennies. This isn’t much different.’

‘But I-’ The woman stopped to wipe away the tears. ‘You’re an angel, missus.’

Annabelle laughed. ‘More like a devil if you knew me. Now, you get yourself over to Mrs Wainwright and warm up.’

‘Thank you. God bless you, missus.’

‘Don’t,’ Annabelle told her. ‘Have yourselves a good Christmas.’

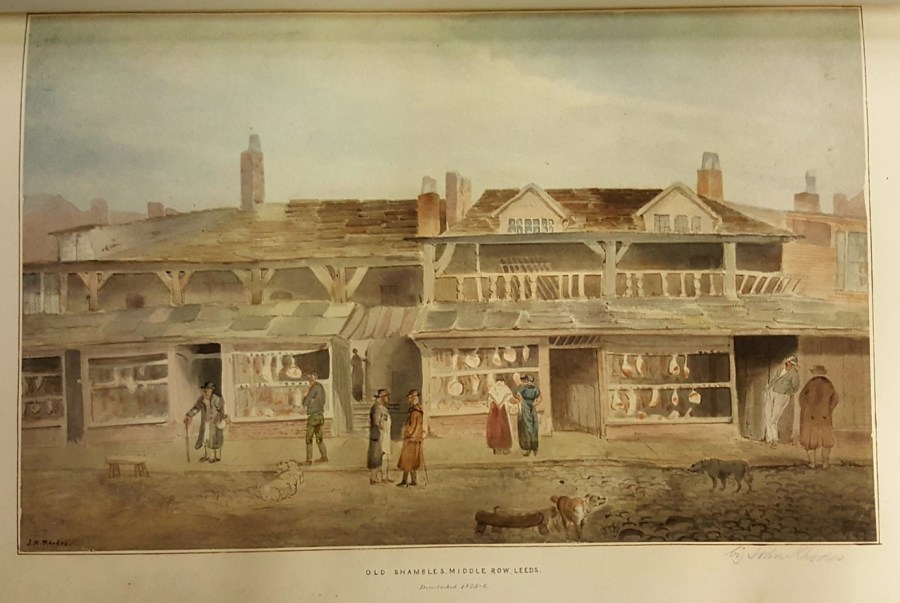

She strode off, drawing her shoulders back, ready to do battle at the brewery. As she walked, she noticed the gaggle of men standing around a metal bin, burning scraps of wood to keep themselves warm and the women outside the pawnbroker’s shop with its three gold balls, clutching clothes and sheets to pledge to keep their families fed during the week. Plenty of poverty in Sheepscar.

She had money. The pub was a little goldmine and her husband was a Detective Chief Superintendent with Leeds City police, making a decent amount. But she couldn’t help everyone. That was why she’d run to be elected as a Guardian, to try and help the poor who were always so vilified.

Not enough, though. It was never enough.

She made a few detours after reading the Riot Act to the owner of the brewery, leaving him red-faced and full of apologies, making promises that she’d receive her proper order.

Howard Winthrop ran a chemical plant over near Skinner Lane. The place stank like the devil’s cauldron, Annabelle thought as she wrinkled her nose. But the man had a good heart and plenty of brass.

She only stayed long enough to invite him to a meeting at the Victoria that evening. The same at Hope Foundry on Mabgate, where she felt overwhelmed by the noise of the machines. She was back behind the bar for the dinner rushing, before popping out to the Prince Arthur just up the road, round to the Pointers, no more than a few yards from her door, then the Roscoe up Chapeltown Road, and finally the vicarage at St Cuthbert’s church.

Eight o’clock and they were all in the living quarters over the pub, chattering until she called the group to order with a spoon tapping across her glass of gin.

‘Thank you for coming at such short notice.’ She looked around the faces, making sure she had their attention. ‘I saw something this morning that almost broke my heart. A mother and her two bairns out on the street. We’re supposed to be the richest country in the world and things like that happen all the time.’ She waited for the objections to flower, then continued. ‘I know we can’t change it all. Not us, sitting here.’ That kept them silent ‘But maybe we can make sure some of them are warm and fed on Christmas Day. Presents for the little ones, too. Look at us here, we’ve all got plenty. More than we need.’ She smiled at them. ‘Money’s not going to do us any good when we’re six feet under, is it? What do you think?’

‘What do you have in mind?’ Winthrop asked as he helped himself to more whisky from the bottle on the table.

‘We all chip in and put on something bang-up.’ Annabelle nodded to the vicar from St Cuthbert’s. ‘I thought we could have it in your church hall.’

‘I imagine we could,’ he agreed after a moment. ‘Not on Christmas Day, though.’ He looked thoughtful. ‘Some of the churchwomen’s guild might be able to help.’

‘If they can’t, we’ll take care of it themselves.’ She drew a piece of paper from the pocket of her dress. ‘I’ve put together some ideas. See what you think.’

*

‘Thirty,’ said Reverend Winterson with a contented smile. ‘I’d call that a very fair turnout, wouldn’t you, Mrs Harper?’

‘Do you think so?’ Annabelle replied doubtfully. ‘There are two or three times that number who could have used the food and the warmth.’ She glanced through the open door to the kitchen where her husband Tom was covered by an apron, arms deep in the sink as he washed the plates, while their daughter Mary dried them. Helping without a complaint, not even a moan.

‘Maybe so, but…’ His voice tailed away as if he wasn’t sure what to say. ‘Thirty is still better than one. We made a difference.’

‘To a few.’ She’d hoped for a huge turnout. Free food, presents for the children. Surely there were plenty who wanted that. The church had put up posters had all across Sheepscar, up into Harehills and Burmantofts, down through the Leylands. All very earnest and serious. Full of religion. Very worthy, with a promise of prayers and hymns to celebrate the birth of the Lord. The kind of Godly folderol guaranteed to put people off when what they wanted was pleasure, an hour or two of relief from life’s grimness.

‘Some people have an unfortunate, prideful attitude to receiving charity,’ the vicar said with a sigh.

‘I suppose they do,’ she said thoughtfully. ‘There’s plenty left over. What are you going to do with it?’

‘Distribute it to the needy,’ he answered.

She smiled. ‘Isn’t that what we’ve just being doing?’ she asked kindly. ‘Look, it’s two days until Christmas. Can you arrange to get it all to the Victoria tomorrow?’

He raised his eyebrows in astonishment. ‘I imagine I can. Why?’

She grinned. ‘Stop by for your Christmas dinner and you’ll see.’

*

Word of mouth. No time for anything more: a Christmas party at the Victoria. No airs or graces, no mention of needy or charity. Everybody invited to have a good time. And it was in a pub, more familiar and welcoming than a church to many round here. On Christmas Eve she’d bribed her regulars with free drinks to help give the place a thorough clean and hang up colourful paper chains. Jingling John had arrived with a few holly boughs to hang. By evening the public bar looked festive. She didn’t ask where the scrawny Christmas tree in the corner had come from; sometimes it was prudent not to know.

Christmas morning, she was up early, making sure everything would be ready. The Victoria wouldn’t be open for paying business today. Annabelle had time to eat breakfast and spend half an hour on gifts. Book and notebooks for Mary, and she looked over the moon to receive them, dashing across the room to hug her parents.

The girl had embroidered handkerchiefs for each of her parents. Decent work, done with love and duty, but the girl would never make a seamstress, her mother thought. Just as well that she had her sights set on other things. Learning to use one of the new typewriters and starting a secretarial agency. One of the modern jobs. She was clever and ambitious; maybe she’d make a success of it.

Tom had surprised her the smart set of gold earrings she’d had her eye on for months. She’d never said anything, but he’d been a good, observant policeman. It was nigh on impossible to buy for him; in the end she’d scrambled around, settling on a fancy paisley silk scarf from the Grand Pygmalion.

On the dot of noon, she unlocked the door. Fires had been burning in the hearths for a couple of hours, every room warm and comfortable. Food on the tables. Nothing hot, but ample to fill plenty of bellies. She just had to hope they’d come.

*

Half an hour and the Victoria was full. Someone was thumping out Nellie Dean on the piano, the big song of the year at the music halls, and voices were singing along, some beautiful and soaring, most hopelessly out of tune. Many of them smiling at her and raising their glasses in a toast.

Annabelle looked around the happy faces and felt a surge of gratitude.

A proper Christmas party. There, almost hidden in the corner, eating a mince pie, the woman she’d seen on Sheepscar Street. The one who’d inspired all this. Baby suckling with contentment at her breast, the older daughter playing with a rag doll.

She felt Tom come up behind her and put his arms around her waist.

‘They’re enjoying themselves,’ he murmured in her ear.

‘So am I,’ she told him with a happy grin. ‘So am I.’

Remember, if you like this, there are 11 novels featuring Tom and Annabelle Harper. There are also two of mine that came out during the year and make great gifts for yourself or people you like. I’d be grateful…what you decide, have a lovely time and a happy and healthy 2026.