It’s the next-to-last of the Christmas stories. I hope you’re enjoying them. I realise that charity has been a theme in them, along with compassion. No regrets about that. It’s right for the season. Meanwhile, take time over your tea and coffee and mince piece while you look at this. Thank you.

‘Excuse me, luv, do you have one like that in a plum colour?’ Annabelle Harper pointed at the hat on display behind the counter. It was soft blue wool, with a small crown and a wide brim, decorated with a long white feather and trailing lace meant to tie under the chin.

The shop assistant smiled.

‘I’m afraid not, madam. We only have what’s on display. ‘I’m very sorry.’

‘Doesn’t matter.’ She put down her purchases, stockings, bloomers, garters, and a silk blouse. ‘I’ll just take those, please.’

Be polite to everyone, that’s what her mother had said when she was younger, and it was a rule Annabelle had lived by. It cost nothing, and a little honey always ensured good service.

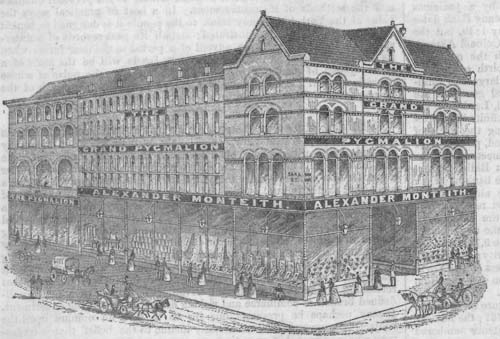

The Grand Pygmalion was packed with people shopping. Women on their own, with a servant along to carry purchases, wives with long-suffering husbands who looked as if they’d rather be off enjoying a drink somewhere.

Four floors, two hundred people to help the customers, wonderful displays of goods. It just seemed to grow busier and busier each year. But it was the only real department store in Leeds. She waited as the girl totted up the totals.

‘I have an account here, luv.’

She saw the quick flicker of doubt and gave a kind smile. Couldn’t blame the lass. She didn’t sound like the type of person with the money to shop here. Then the gaze took in her clothes and jewellery and the girl nodded.

‘Of course, madam. What name is it?’

‘Mrs. Annabelle Harper. The address is the Victoria public house on Roundhay Road.’

Everything neatly packed and tied into a box, she walked out on to Boar Lane. A fortnight until Christmas and it was already cold. Bitter. A wind whistled along the street from the west. All around her she could hear people with their wet, bronchitic coughs. It’d probably snow soon enough, she thought.

Omnibuses, trams, carts and barrows moved along the road, a constant clang of noise. On the corner with Briggate, by the Ball-Dyson clock, a Salvation Army brass band was playing, their trumpets and tubas competing against the vehicles and the street sellers crying their goods.

She pulled the coat closer around her body as she walked, clutching the reticule tight in her hand. Plenty of crime this time of year. Married to a detective inspector, she couldn’t help but hear about it. And she had enough cash with her for something special; she didn’t want to lose that.

Strolling up towards the Headrow, all the lights in the shops were already glowing. Only three and it was almost dark. Roll on spring, she thought, then stopped herself. Never wish the days away. Who used to say that? She racked her brain. Come on, Annabelle told herself, you’re not old enough to forget things yet.

Then it came. Old Ellie Emsworth at Bank Mill. Annabelle was ten, she’d been at the mill a year, working as a doffer, still too young to be on the machines. Six days a week, twelve hours a day for not even two bob a week when all she wanted to be was out there, away from it all. Ellie had worked the loom all her life. She was probably no more than thirty-five but she looked old, worn-down.

‘I know you don’t like it here,’ Ellie had said to her one day as they ate their dinner. Bread and dripping for Annabelle, all her family could afford. ‘But don’t go wishing the days away. They pass quick enough, lass. Soon you’ll wish you had them back.’

She smiled. For a moment she could almost hear Ellie’s voice, rough as lye soap.

People pressed around her as she walked, some of them smiling with all the joy of the season, others glum and po-faced. Christmas, she thought. They’d never had the money to make a proper do of it when she was little. As soon as she had a little, after she’d married the landlord of the Victoria, she’d given presents and spent all she could afford.

Even the Christmas after he died, she’d been determined to put on a brave face. A big meal for friends, presents that saw their eyes shine. It made her happy.

And now she had Tom. She had the wedding ring on her finger and she felt happier than she had in a long, long time. This was going to be their first married Christmas and she was going to buy him something he’d never forget. A new suit. A beautiful new suit.

Along New Briggate, across from the Grand Theatre, the buildings were bunched together. Business on top of business as the floor climbed to the sky. Photographers, an insurance agent, gentleman’s haberdasher. You name it, it was all there if you looked hard enough.

The girl stood in the doorway of number fifteen, a broken willow basket at her feet. At first Annabelle’s glance passed over her. Then she looked again. For a moment she was taken back twenty years. She was ten again and staring at Mary Loughlin. They’d gone to school together, started at the mill together, laughed and played whenever they had chance. The same flyaway red hair that the girl had tried to capture in a sober bun. The same pale blue eyes and freckles over the cheeks. The same shape of her face.

‘Wreath, ma’am?’ The girl held it out, a poor thing of ivy and holly wrapped around a think branch of pine. ‘It’s only a shilling,’ she said hopefully.

Her wrist was thin, the bones sticking out, and her fingers were bare, the nails bitten down to the quick, flesh bright pink from the cold. An old threadbare coat and clogs that looked to be too small for her feet.

‘What’s your name, luv?’

The girl blushed.

‘Please ma’am, it’s Annabelle.’

For a second she couldn’t breathe, putting a hand to her neck. Then, very gently she shook her head.

‘Your mam’s called Mary, isn’t she?’

The girl’s eyes widened. She stared, frightened, tongue-tied, biting her lower lip. Finally she managed a nod.

‘She was, ma’am, yes.’

‘Was? Is she dead?’

‘Yes, ma’am. Three year back.’

Annabelle lowered her head and wiped at her face with the back of her gloves.

‘I’m sorry, luv,’ she said after a while. ‘Now, how much are these wreaths?’

‘A shilling, ma’am.’

‘And how many do you have?’

‘Ten.’

She scrambled in her purse and brought out two guineas.

‘That looks like the right change to me.’ She placed them in the girl’s hand. Before she let go of the money, she asked, ‘What was your mother’s surname before she wed, Annabelle?’

‘Loughlin, ma’am.’

‘I tell you what. There’s that cocoa house just across from the theatre, Annabelle Loughlin. I’d be honoured if you’d let me buy you a cup. You look perished.’

The girl’s fingers closed around the money. She look mystified, scared, as if she couldn’t believe this was happening.

‘Did your mam ever tell you why she called you Annabelle?’

‘Yes ma’am.’ For the first time, the girl smiled. ‘She said it was for someone she used to know when she was little.’

Mrs. Harper leaned forward. Very quietly she said,

‘There’s something I’d better tell you. I’m the Annabelle you’re named for.’

She sipped a mug of cocoa as she watched the girl eat. A bowl of stew with a slice of bread to sop up all the gravy, then two pieces of cake. But what she seemed to love most was the warmth of the place. Young Annabelle kept stopping and looking around her, gazing at the people and what they had on their plates.

She was twelve, she said. Two older brothers, both of them working, and two younger, one eight and still at school, the other almost ten and at Bank Mill.

‘What does he do there?’

‘He’s a doffer,’ the girl said and Annabelle smiled.

‘That’s what your mam and I did when we started. Finally I couldn’t stand it anymore and went into service.’

‘But you’re rich,’ the girl said, then reddened and covered her mouth with her hand. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘I’ve got a bob or two,’ she agreed. ‘I was lucky, that’s all.’ The girl finished her food. ‘Do you want more?’

‘No ma’am. Thank you.’

‘And don’t be calling me ma’am,’ she chided gently. ‘It makes me feel old. I’m Annabelle, the same as you. Mrs. Harper if you want to be formal.’

‘Yes, Mrs. Harper.’

‘What does you da do, luv?’

‘He’s dead.’ There was a sudden bleakness in her voice. ‘Two years before my mam. So me and Tommy, he’s the oldest, we look after everything.’

Annabelle waved for the bill and counted out the money to pay as the girl watched her.

‘What work do you do? When you’re not selling wreaths, I mean.’

‘This and that ma’a – Mrs. Harper.’

‘And nothing that pays much?’ The girl shook her head. ‘You still live on the Bank?’

‘On Bread Street.’

‘Can you find your way down to Sheepscar?’

‘Course I can.’ For a second the bright, cheeky spark she remembered in Mary flew.

‘Good, because there’s a job down there if you want one. I own a pub and a bakery down there, and someone left me in the lurch.’ The girl just stared at her. ‘It’s not charity, you’ll have to work hard and if you’re skive you’ll be out on your ear. But I give a fair day’s pay for a fair days’ graft. What do you say?’

For a second the girl was too stunned to answer. Then the words seemed to tumble from her mouth.

‘Yes. Thanks you ma’am. Mrs. Harper, I mean. Thank you.’

Annabelle looked her up and down.

‘If you’re anything like your mam you’ll be a grand little worker.’

‘I’ll do my best. Honest I will.’

‘I know, luv. You’re going to need some new clothes. And I daresay the rest of your lot could use and bits and bobs, too.’ She took a five pound from her purse and laid it on the table. ‘That should do it.’ The girl just stared at the money. ‘Don’t be afraid of it,’ Annabelle told her. ‘It won’t bite. You buy what you need.’

‘Do you really mean it?’ The words were barely more than a whisper.

‘I do.’ She grinned. ‘When I saw you, it was like looking at Mary all over again. Took me right back. You’re just as bonny as she was.’ She stood, the girl quickly following. ‘You be at Harper’s Bakery at six tomorrow morning. Mrs. Harding’s the manager, tell her I took you on. I’ll be around later.’

‘Yes, Mrs. Harper. And…thank you.’

‘No need, luv. Just work hard, that’s all I need. You get yourself off to the Co-op and buy what you need.’

The girl had the money clenched tight in her small fist. At the door, before she turned away, she said,

‘Mrs. Harper?’

‘Yes, luv?’

‘Sometime, will you tell me what my mam was like when she was young?’

‘You know what? I’d be very happy to do that.’

She watched the girl skip off down the street. Who’d have thought it, Mary calling her lass Annabelle? She shook her head and looked up at the clock. A little after four. She still had time to go to that tailor’s on North Street and order Tom a new suit for his Christmas present.