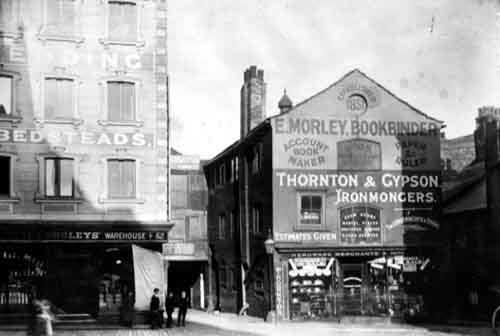

Leeds, 1896

Annabelle Harper had gone five paces past the man before she stopped. There were beggars everywhere in Leeds, as common as shadows along the street. But something about this face flickered in her mind and lit up a memory. He was despondent, at his wits’ end, but unlike so many, he wasn’t trying to become invisible against the stones, to disappear into the fabric of the city. He might not like he was happy about it, but the man was very much alive. She stopped abruptly, turned on her heel in a swish of crinoline and marched back until she was standing over him, shopping bags dangling from her hands. It was the last day of February, a sun shining that almost felt like spring.

‘You, you’re Tommy Doohan, aren’t you?’

Very slowly, as if it was a great effort, he raised his head. He’d been staring down at the pavement between his legs.

‘I am,’ he answered. His voice was weary, a broad Leeds accent with just the smallest hint of Ireland, easy to miss unless you were familiar with it. He stared up at her, baffled, with his one good eye, the other no more than a small, dark cavern above his cheek. ‘And who might you be? You don’t look familiar.’

‘Annabelle Harper,’ the woman replied. ‘Little Annabelle, when you knew me. Back on Leather Street where we were little.’

His smile was weak. He looked as if the entire weight of the city had pressed down on him and left him small and broken. It had dropped him in this spot

‘That was a long time ago.’

His suit had probably been reasonably smart once. Good, heavy wool, but the black colour had turned dusty and gritty from sitting so long. Cuffs and trouser hems frayed, threads hanging to the ground. Up close, she could see the grime on his shirt, no collar, no tie. The shine had long vanished from his shoes. He was bare-headed, his hair dark, growing wild and unruly. His cap sat upside-down between his thighs. In a rough, awkward attempt at copperplate, the cardboard sign propped against it read: But give that which is within as charity, and then all things are clean for you.

‘Luke,’ she said. ‘Chapter eleven, verse forty-one.’ Annabelle grinned. They’d been in the same class at Mount St. Mary’s School. ‘The nuns must have rapped my knuckles a dozen times over that one. Sister Marguerite would be happy it finally stuck.’

‘Ah, she did the same to me as well. Twenty times, at least. But they’d have a harder time doing that now.’ He held up his right arm, the hand missing two fingers and the thumb.

Annabelle took a slow, deep breath.

‘My God, Tommy, what happened?’

‘Just a little fight with a machine,’ he said wryly. ‘I think I won, though. You should have seen the machine when we finished.’

‘How can you-’ she began, then closed her mouth. She knew the answer deep in her bones. You laughed about it to stop the pain. You joked, because if you didn’t you’d fall off the world and never find your way back. ‘Come on, I’ll buy you a cup of tea.’

‘I can’t let a woman pay for me.’

She dropped the bags and stood, hands on her hips, face set.

‘You can and you will, Tommy Doohan. Get off your high horse. You’d have been happy enough if I’d put a tanner in your cap. Now, up on your feet.’ She looked along the Upper Head Row and across down Lands Lane. ‘We’re going to that place over there. And I’m not taking no for an answer.’

For a moment he didn’t move. But her voice had a razor edge, and he pushed himself to his feet, scooping a couple of pennies and farthing from the cap before he jammed it on his head.

He was tall, towering a good nine inches above her. Close to, he smelt of dirt and decay, as if he might be dying from the inside.

‘I’d carry your bags for you, but one of the paws doesn’t work so well.’

‘Give over,’ she told him, and his mouth twitched into a real smile.

He cradled the mug, as if he was relishing the warmth, only letting go to eat the toasted teacake she’d ordered for him. When he was done, he wiped the butter from his mouth with the back of a grimy hand, then felt in his pocket for a tab end.

They’d been silent, but now Annabelle said: ‘Go on, Tommy, what happened to you?’

‘When I was sixteen, I headed over to Manchester to try my luck. Me and my brother Donald, do you remember him?’

She had the faint recollection of someone a little older, tousle-haired and laughing.

‘What could you do there that you couldn’t here?’

‘It was different, wasn’t it?’ he said bitterly. ‘I’d been a mechanic down at Black Dog Mill, I could fix things, and Donny, well, he was jack of all trades.’ He smoked, then stubbed out the cigarette in the ashtray in quick jabs. ‘We did all right, I suppose. One of the cotton mills there took him on, made him a foreman, earning fair money.’

‘What about you?’

‘Down at the docks. Long hours, but it was a decent wage. Lots of machines to look after. I met a lass, got wed, had ourselves a couple of kiddies.’

‘I’ve got one, too. A little girl.’

Doohan cocked his head.

‘What does your husband do? You look well off.’

‘You’ll never credit it.’ She laughed. ‘He’s a bobby. A detective inspector. And I own a pub. The Victoria down in Sheepscar.’

He let out a low whistle. ‘You’ve turned into a rich woman.’

‘We get by,’ Annabelle said. ‘Anyway, what about your family?’

‘Gone,’ he told her bleakly. ‘About two years back I was working on this crane, you know, hauling stuff out of the boats. The mechanism has jammed. I almost had it fixed when the cable broke. It’s as thick as your arm, made from metal strands. Took the fingers before I even knew it, and a piece flew off into my eye.’ He shrugged. ‘I was in the hospital for a long time. Came out, no job. They told me that since I didn’t have two full hands, I wasn’t able to do the work anymore. Goodbye, thank you, and handed me two quid to see me on my way like I should be grateful.’

‘Where was your wife?’

‘Upped sticks and scarpered with my best mate as soon as someone told her I wasn’t going to be working. Took the children with her. I tried looking round for them for a long time, but I couldn’t find hide nor hair. Finally I thought I’d come back to Leeds. I might have a bit more luck here.’ He sighed. ‘You can see how that turned out. On me uppers on the Head Row. Begging to get a bed.’ He spat out the sentence.

‘Couldn’t your brother help?’ Annabelle asked.

‘Donald was married, and he and his brood had gone off to Liverpool. He has his own life, it wouldn’t be fair. Me mam and dad are dead, but there are a few relatives who slip me a little something.’

She stayed silent for a long time, twisting the wedding ring back and forth around her finger.

‘How long did you work at all this?’

‘Seventeen years,’ Doohan said with pride. ‘Ended up a supervisor before…’ He didn’t need to say more.

‘Do you know Hope Foundry? Down on Mabgate?’

‘I think I’ve seen it. Why?’

‘Fred Hope, one of the owners, he drinks in the pub. He was just saying the other day that he’s looking for engineering people. You know, to run things.’

Doohan raised his right arm with its missing fingers to his empty eye.

‘You’re forgetting these.’

‘No, I’m not. You’ve got a left hand. And your brain still works, doesn’t it?’

‘Course it does,’ he answered.

‘Then pop in and see him tomorrow. Tell him I suggested it.’

He stared at her doubtfully. ‘Are you serious about this?’

‘What do you think?’

‘He’ll say no. They always do.’

‘Happen he won’t. Fred has a good head on his shoulders. He can see more than a lot of people.’ Annabelle opened her purse and pulled out two one-pound notes. ‘Here. It’s a loan,’ she warned him. ‘Just so you can get yourself cleaned up and somewhere decent to sleep. Some food in you.’

‘I can’t.’

She pressed the money into his palm.

‘There’s no saintliness in being hungry and kipping on a bench,’ she hissed. ‘Take it.’

He closed his fingers around the paper.

‘I don’t know what to say. Thank you. I’ll pay you back.’

‘You will,’ she agreed. ‘I know where you’ll be working. And your boss is a friend of mine. Now you’d better get a move on, before the shops shut.’

‘What about…?’ He gestured at the table.

‘Call it my treat. Now, go on. Off with you.’

At the door he turned back, grinning. He seemed very solid, filling the space.

‘Is this what they mean by the old school tie?’

Forgive the self-promotion, but it’s almost Christmas and Amazon has my newest book on sale (I’d prefer you to give your money to a local bookshop but…) for a low price, hardback and Kindle. If you want to give it a try, find it here.