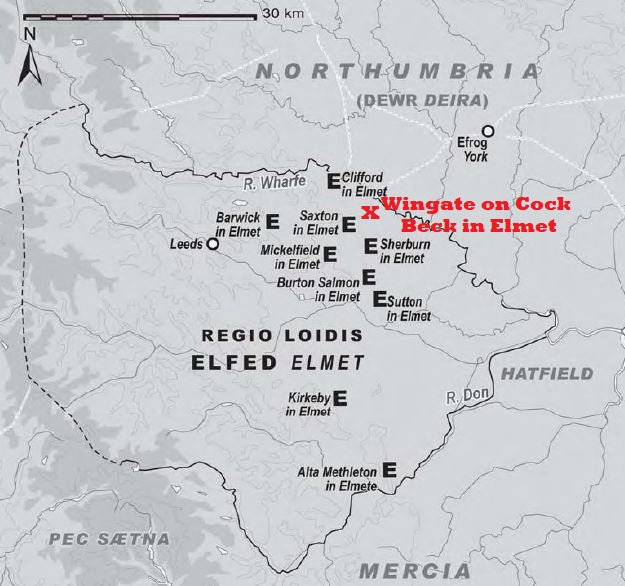

Barwick-in-Elmet, Sherburn-in-Elmet. The Parliamentary constituency of Elmet and Rothwell.

Fine, but where was Elmet? You can ask the question, but nobody can give you an exact answer. A similar area to the old West Riding (which included much of South Yorkshire)? Somewhere from Leeds to Selby? The poet Ted Hughes believed its heart was in the Calder Valley. Something that’s recorded in the tribal hidage is that it was 600 hides, which is a value rather than geographical measurement. Even so, it was small.

It was a British kingdom that abutted Saxon ones, but it was also a forest, according to Bede. It might have existed before the Romans came. Some many possibilities, but so little fact.Certainly it had its own rulers. However, we know of very few people from Elmet. Two of them were warriors mentioned in great the Welsh epic, Y Gododdon: Gwallog ap Leenog (ap meaning son of) and Madog Elfed. There was also a king of Elmet named Ceredig ap Gwallog. Bede mentions that after Gwallog’s “subsequent kings made a house for themselves in the district, which is called Loidis ” – the first written mention of the area that became Leeds, at least in a very general sense.

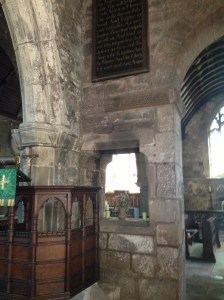

Bede also mentions “the monastery the lies in Elmet wood” and it’s possible that might be a reference to the ancient church at Ledsham. The south date, which leads into the west tower, dates from around 700 CE (making it the oldest building in West Yorkshire), and much of the original nave survives.

While there’s nothing to indicate Elmet’s origins, it seems virtually certain that it vanished somewhere after 616-17, thanks to Edwin of Northumbria, possibly by invitation, but it possibly by negotiation. Yet, as Bede shows, the Elmet name remained more than a century later.

It’s possible – but not substantiated – that it might have regained its independence after Edwin’s death and remained that way until Viking times, which might explain the names of the small towns.

Curiously, it received another mention in 1315 in a Florentine bill of sale for wool, where it’s curiously distinct from Leeds.

d’Elmetta (Elmet) 11 marks per sack

Di Ledesia (Leeds) 12½ marks per sack

di Tresche (Thirsk) 10½ marks per sack

de Vervicche (York) 10½ marks per sack.

I’m grateful to Lost Realms by Thomas Williams for some of the information here.

Some advertsing, I’m afraid. The holidays are coming, and books always make ideal gifts. If someone you like enjoys history and crime, why not buy them A Dark Steel Death, the most recent book in my Tom Harper series. They won’t be disappointed, I promise. Your local independent bookshop can order it or, you can find the cheapest price online here (with free UK shipping).

Thank you.