My newest book, A Dark Steel Death, takes place at the start of 1917. It’s a crime novel, but also a war novel – the war on the home front, where things were bleak. The Battle of the Somme the year before had killed and wounded so many of the young men from Leeds; it was said there wasn’t a street in the city that the fighting there hadn’t touch in some way.

But there was more going on the in the world. In Russia, the February Revolution (actually early March in the modern calendar) began to change everything in the country; November would cause a second, final rupture. In Britain, there was plenty of support from the labour movement, with an event held at London’s Albert Hall, attended by 10,000, with another 5,000 outside.

A second, known as the Leeds Convention, was set for June 3, organised by the United Socialist Council, made up of member of the British Socialist Party, the Independent Labour Party, and the Fabian Society.

I toyed with the idea of having that as the backdrop to a book set in 1917. Possibly one of the delegates might have been murdered, or someone protesting the convention. In the end, portraying the outside events in Russia felt a little too complex, and the idea held echoes of the backstory to Gods of Gold. I feel I made the right decision, but this remains a fascinating bit of Leeds history.

The intention was to hold it in Leeds’ Albert Hall – the big room in what was then the Mechanics’ Institute (now Leeds City Museum).

That was where the problems began. Unsurprisingly, the government didn’t want anything like this to happen in the middle of a war. They feared the idea of revolution could spread. They mooted the idea of banning it completely, but didn’t.

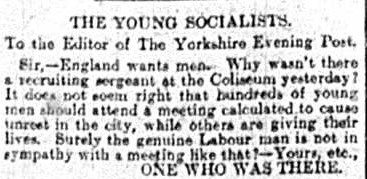

Instead, Leeds City Council refused to allow the use of the Albert Hall and ordered all hotel owners to refuse bookings from delegates, and they seemed to gladly comply. The police banned public meetings; anything to try and prevent things moving ahead (in the on, on the Saturday evening, the police asked hoteliers to sell room to delegates who had nowhere else to sleep). The press had no kind words for the delegates or the subject matter.

However, the Leeds Convention, as it came to be known, did happen. The organisers booked the Coliseum, where Prime Minister Asquith had spoken in 1908 (see The Molten City) and locals opened their homes to delegates.

The local papers came out against the convention, as did some of the national dailies.

The Leeds Weekly Citizen offered a full account of the proceedings, also detailed in the book British Labour and the Russian Revolution (which was reissued in 2017). In the end, 1500 delegates debated four motions. Some big names appeared, including Ramsay MacDonald, Herbert Morrison, Sylvia Pankhurst and Bertha Quinn, who’d go on to become a Labour councillor in Leeds.

Everything went off peacefully, which was more than something else happening in the city over the same weekend – three nights of anti-Jewish rioting. A little about that in weeks to come, another lesser-known and awful incident in the city’s history.

A curious aside: a writer from Leeds was in Russia during and after it all, and came to known the top people. There were rumours that he might also have been a British Intelligence agent as well as a reporter. His name? Arthur Ransome (yes, Swallows And Amazons).

A Dark Steel Death won’t take you inside the Coliseum for the convention, but it will put you on the dangerous and deadly winter streets of Leeds at the start of 1917.

I’d be very grateful if you’d buy a copy or ask your library to stock it.