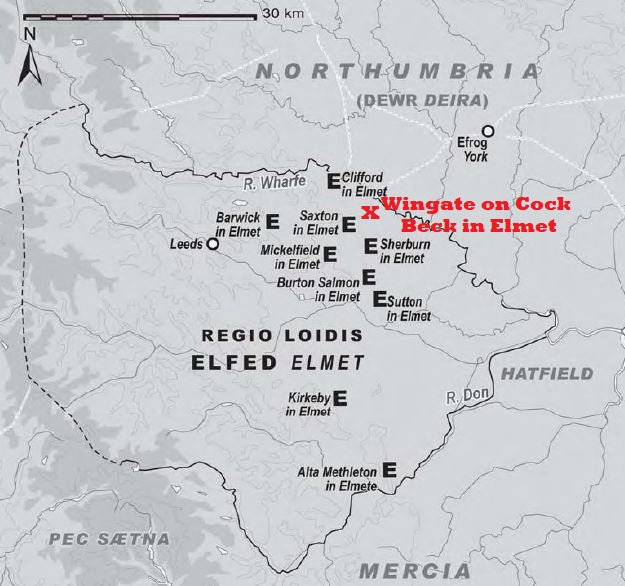

Christmas is over, but a lot of you are probably still off work, scuffling around and wondering how to fill your time. Since it’s still somewhat the season of goodwill to all men and women, here’s a Leeds story to entertain you for a few minutes. It dates from the time when Saxons and Vikings lived in the area, when Leeds was Loidis, on the boundary of kingdoms, and York was Jorvik.

I’d expected a mean little place, like the other Saxon villages in the kingdom. But as we approached, with the horses whinnying at some smell or other, it took me by surprise.

It was neat, cleaner than I’d imagined. The people looked well-fed, eyeing us with quiet suspicion as we arrived. Five of us, me and four warriors, frightening, intelligent men with piercing eyes and dark glances. They’d proved themselves in battle often enough. A good escort for a holy man.

The church was wood, rough-hewn but carefully built. Their God might not be ours, but they worshipped him well. And outside stood five tall stone crosses, heavily carved and decorated with ornaments, scrolls and figures. I could pick out Weyland the Smith in one, from the story they love to tell at night. On others, there were angels, men, who knew what.

I dismounted, looking around. A man approached me hesitantly, bowing his head a little.

‘You’re welcome here, my Lord,’ he said. ‘I’m Hereward. The thane here.’

‘Gunderic.’ I nodded at him. ‘Where are they?’

‘Not here yet. One of my men spotted them a few minutes ago, still two miles away. Would you like something to drink after your ride?’

A girl came with a jug of ale and mugs. Out here we were on the edge of the kingdom. Our land, the Norse land, ended at the river a few yards away and on the hills to the west. It was autumn weather, most of the leaves already fallen, the branches as barren as crows. A grey sky and always the promise of rain on this damned island.

‘King Erik, is he well?’ Hereward asked. Inside, I smiled. Erik’s name was one to make any Saxon nervous. The Bloodaxe, they called him. It was true that he’d used the weapon often enough, but not for a few years now. These were the days of ruling, of words and diplomacy. Instead of the longships, we made marriage with the locals. I had, and Erik, too. His wife was the daughter of a nobleman from Strathclyde.

‘He’s in good health. Still strong as an ox.’ Keep them wary of the man I’d served for twenty years, in Denmark and now here. We’d started as raiders and now people fawned in front of us. We were starting out own dynasties in Jorvik, a kingdom that might include all of England one day.

But not yet. That was why I was in this village of Loidis, standing close to the river, waiting to conduct a favoured guest back to meet my master.

‘This church of yours,’ I said, walking towards it. ‘What are these crosses for?’ I’d been all over the area in the last few years, but I’d never seen anything quite like this.’

‘To commemorate men who’ve died, Lord,’ Hereward answered. ‘Their sons have them carved as memorials.’

‘Why here?’ I wondered.

‘There’s a ford at the river.’ He pointed to a shallow area of the water. ‘Plenty of people cross here. Some stay.’

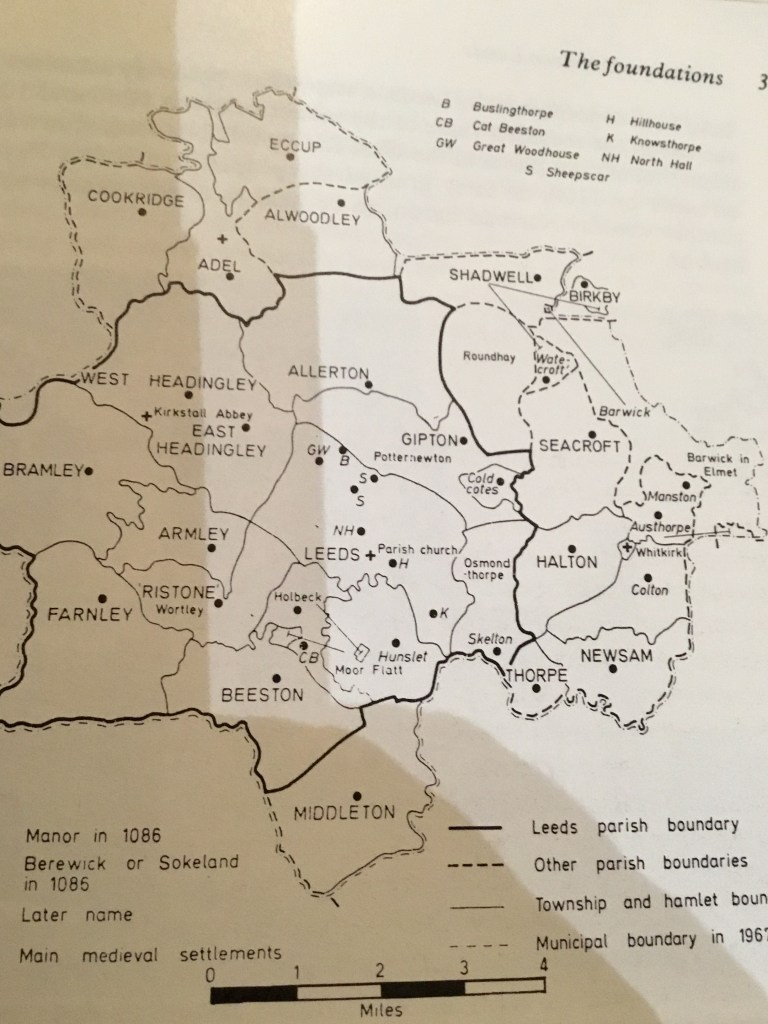

Not many, from the look of the place. Houses spread in a line away from the church. Clean enough, yes, but hardly busy. I doubted there could be more than two hundred people in the whole of Loidis. But it had the church, more than most of these places. And it had these strange crosses.

A man ran up and spoke to Hereward.

‘Cadoe will be here in a minute. King Domnall’s come with him.’

I straightened my back. Royalty to escort the holy man? I hadn’t expected that. They treated him with honour, so we had to do the same. But I was an important man in this kingdom. Not a king, perhaps, but certainly a lord, with lands of my own.

Ten of them. Domnall, his housecarls, heavily armed and glanced around constantly. They eyed my warriors with suspicion. And on a small mare, a thin man, simply dressed, his wild hair going grey. Cadroe. The holy man.

At first he didn’t seem so remarkable. Then he turned to gaze at me and I saw his eyes. There was something in them, some fire, some certainty and passion. I’d never seen a look like it before.

But I knew my graces. First a bow to greet the king.

‘Your Majesty.’ My voice was loud enough for everyone to hear. ‘I’m Gunderic, sent by King Erik to make sure his guest reaches Jorvik safely. He welcomes you all to his kingdom.’

No answer, other than a short nod of acknowledgment. I turned to Cadroe.

‘My master looks forward to meeting and talking with you, sir.’

‘And I look forward to seeing my dear Æthelberta again.’ His eyes twinkled.

‘My Lord?’

‘Not Lord, not Sir. I don’t have a title and don’t want one,’ he said.

‘You’re related to the king’s wife?’ I’d never heard this.

‘Distantly, but yes. I’m related to Domnall, too.’ He tilted his head towards the king who was talking to the thane. ‘And we’re all God’s children, too.’ For a moment I thought he was teasing. But the smile on his lips wasn’t mocking me.

‘King Erik is expecting us in Jorvik,’ I told him, looking up at the sky. We’d spent the night in Sherburn and set out early to meet Cadroe; we’d be expected before nightfall.

‘Of course,’ he agreed. ‘But first, please, I’d like to preach for the people here. They rarely see a priest.’ He looked at me. ‘For their souls.’

Who was I to disagree? Treat him with respect; those had been my orders. As long as he didn’t take too long, we’d have time.

A work with Hereward, the sharp ringing of the bell that seemed to fill the sky. Another few minutes and the villagers came. A rag-tag bunch, the children as filthy as boys and girls anywhere. The women scared, full of tales about the Northmen. The men all farmers, with rough hands and weatherbeaten skin.

Once they’d gathered, Cadroe stood in front of the crosses and began to speak swiftly in his Saxon tongue. I spoke it passingly well – I had a Saxon wife myself, and my children switched between Norse and Saxon as if they were one language – but it always seemed ugly and guttural to my ears.

But a strange thing happened. As Cadroe spoke, it seemed to make on a musicality, a beauty I’d never noticed before. His words came quickly, too fast for me to follow them all. I glanced at the man quickly, then again. Before, he’d seemed small, someone not to be noticed in a crowd. Now he seemed taller, broader, and it seemed there was a light around him. I closed my eyes then looked again. But it was still there.

He spoke for five minutes, standing in front of those carved memories to man. I could understand how people thought him holy. There was some quality about him, something larger than any of us there, bigger than flesh, deeper than blood.

Cadroe finished with the sign of the cross and the words, ‘May God go with you and protect you.’

And then, as his mouth closed and he began to walk towards me, he became an ordinary man again, with his grey hair, the lines on his face and thin body.

I didn’t understand it. I couldn’t explain it. But I’d ask him on the journey. We had ample time in the saddle ahead of us.

In less than five minutes we were ready to leave. Before I could mount my horse, though, Domnall beckoned me over.

‘My Lord?’ I asked.

‘You saw, didn’t you?’ I opened my mouth to lie, but he continued, ‘I watched your face. He has the message of God on his tongue for all who’ll listen. Please, make sure your king listens to him.’

‘That’s my Lord’s choice,’ I reminded him.

‘Of course.’ Domnall smiled easily. ‘But give your Lord one message from me, please. Tell him that men prosper more in peace than in war.’

‘I will, your Majesty.’

I climbed into my horse and we began to ride away.

Historical note: In the Life of St. Cadroe, he’s remembered as crossing between the kingdom of Strathclyde (ruled by Domnall) and the Norse kingdom (ruled by Eric Bloodaxe) at Loidis – the Saxon name for Leeds. It was a village on the border, used for crossings, and that gave it stature, even if it was still very small. When Leeds Parish Church was being rebuilt in 1838 workmen discovered pieces from five stone crosses that were dated back to the ninth and 10th centuries. The fragments have been put together to make the Leeds Cross, which now stands in Leeds Minster.

These could have been preaching crosses, which predated churches. But those would generally have come from an earlier period. It’s far more likely that they were memorials erected to commemorate important people. Why would that be in Leeds? We’ll never really know, but it’s an indication that the village had real value importance, certainly to the wealthy individuals who commissioned the crosses.