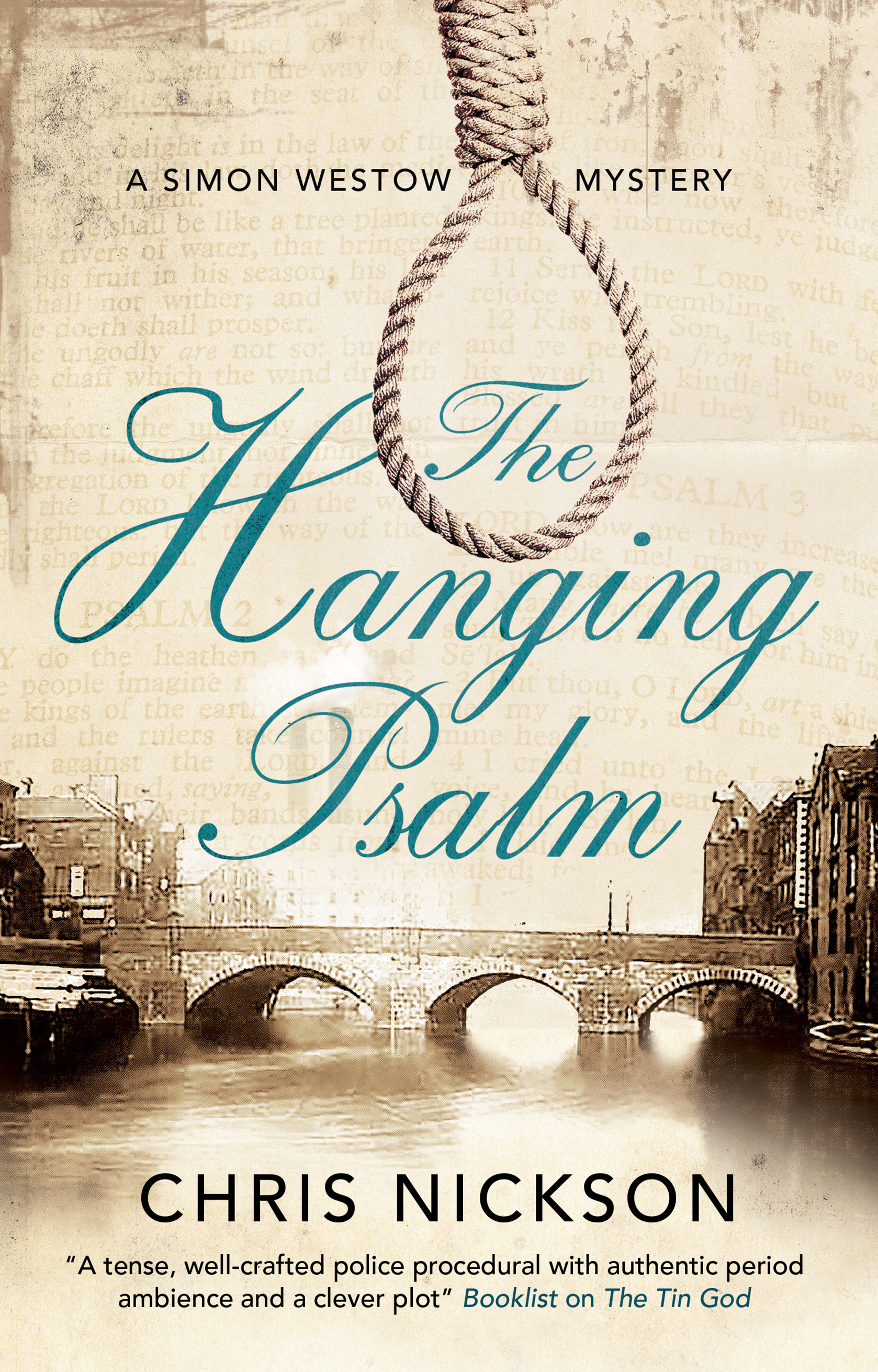

As a novelist, one of the things I’ve tried to do is give a voice to the voiceless in Leeds, and to celebrate those who made a difference to people in this town. It’s why one of my proudest achievements was to be associated with The Vote Before the Vote exhibition in 2018, celebrating local women who worked toward the vote during the 19th century.

One woman who should be known and lauded round here is Alice Mann. She was a radical bookseller and printer. The newspapers and magazines she sold and some of the pieces she printed did what I admire: raised the cry of those who usually went unheard. She stood up for her principles; she even went to prison for them.

Yet most people have never heard her name.

We do we know about her?

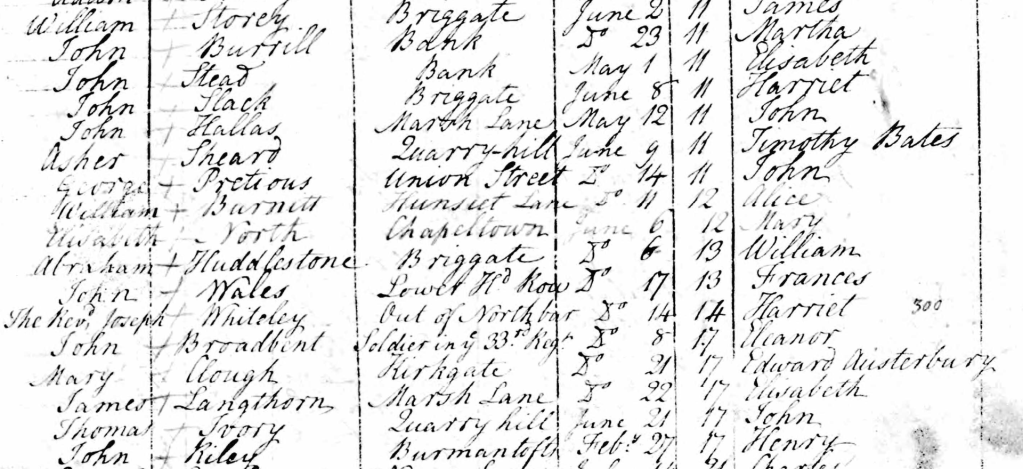

She was born Alice Burnett on Hunslet Lane in 1791, and her father’s name was William. There’s no trail to follow for him, and Alice’s mother isn’t named.

In 1807 she married James Mann at Leeds Parish Church.

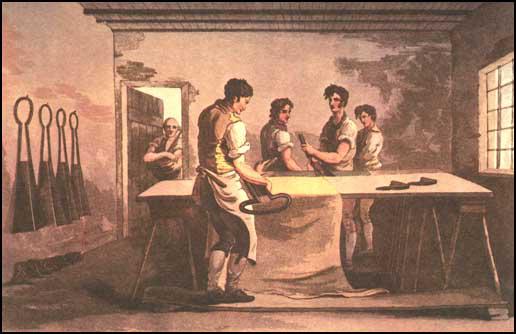

Who was James Mann? Born in Huddersfield (or possibly Leeds, on Briggate) in1784, he was employed as a cloth dresser, a man who cropped the finished woven cloth. It was a skilled trade that paid a handsome wage; the croppers had to wield large shears and do their work with concentration and exactitude -and great arm strength. The croppers were among the elite of cloth workers.

Becoming Radicals

The job of cropper was dying. Machines were coming in that could do the work faster and cheaper. This was the time of the machine breakers, the Luddites. Men who wanted to stop industrialisation. It was a forlorn hope. The gates had opened and the flood was coming. But it gave rise to broader issues that would result in Chartism later in the 19th century.

By 1812, the couple were apparently Radicals. They were reputedly involved in a riot on Briggate, where the market was held every Tuesday and Saturday.

England was in the middle of its war against Napoleon. The price of corn (wheat) kept rising and rising, with no check. Bread was a staple food and people couldn’t afford it.

The Manns possibly organised the riot, encouraging people to take the the food. Alice might had led it all, dressed up as “Lady Ludd.” Others claim it was James in a dress. A report in the Ipswich Journal claimed that on August 18:

In the afternoon [in Leeds] a number of women and boys, headed by a female who was dignified with the title of Lady Ludd, paraded the streets, beating up for a mob.

In 1819 the Manns opened a bookshop on Briggate. That was the year of the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester, and government fears over agitation for reform. By then, the Manns had a reputation. The Leeds Intelligencer claimed that their “house appears to be the head quarters of sedition in this town.”

James was a speaker on parliamentary reform, and also an advocate of female reform societies. In 1820 he was successfully prosecuted under the new Six Acts for sedition. While he was travelling around West Yorkshire, Alice apparently kept the shop and looked after the nine children the couple would eventually have (six are listed in the 1841 census, ranging from 23 to 11, along with another child and a lodger).

In 1832, cholera swept through the country. It killed James Mann on August 2, and he was buried at Mill Hill Chapel – apparently a convert to Nonconformism.

The Second Act

Alice still had a family to raise. She needed the bookshop more than ever, and began working with Joshua Hobson, another Radical journalist/printer/bookseller, who moved to Leeds from Huddersfield. He published Voice of the West Riding, and was prosecuted three times for selling an unstamped newspaper.

He set up in business on Market Street – about where Central Arcade is these days – and became active in politics in the town. Alice, meanwhile, had also been in court for selling unstamped papers. In 1834 she ended up being sentenced to seven days in the House of Correction in Wakefield. Two years later she was offered a deal where most of the charges would be dropped if she agreed to stop selling unstamped papers. She refused, saying selling books and papers was her only way to support her family. She was sentenced to six months in prison at York Castle. According to the Leeds Intelligencer, a public dinner was held up on her release.

She’d moved premises from Briggate to the new Central Market on Duncan Street, and lived in Trinity Street (or Court, according to the trade directory).

As a jobbing printer, she took on whatever jobs came her way, and repeatedly tried to become printer to the council, a lucrative position, which she won in 1842.

By the 1851 census, she and her family were living in Woodhouse. One blogger has speculated she might have been the author of The Emigrant’s Guide (you can read the piece here), published in 1850. It’s possible, although the evidence is scant. But she had to make a living.

However, she remained true to her roots, supposedly becoming printer of the Leeds Times after its 1839 sale. She was responsible for publishing The Ten Hour Advocate and Mann’s Black Book of the British Aristocracy, among a number of others.

Although any contributions she made haven’t been unearthed, she was almost certainly involved in the Chartist movement in the 1840s, which was strong in Leeds (where the Northern Star newspaper was published).

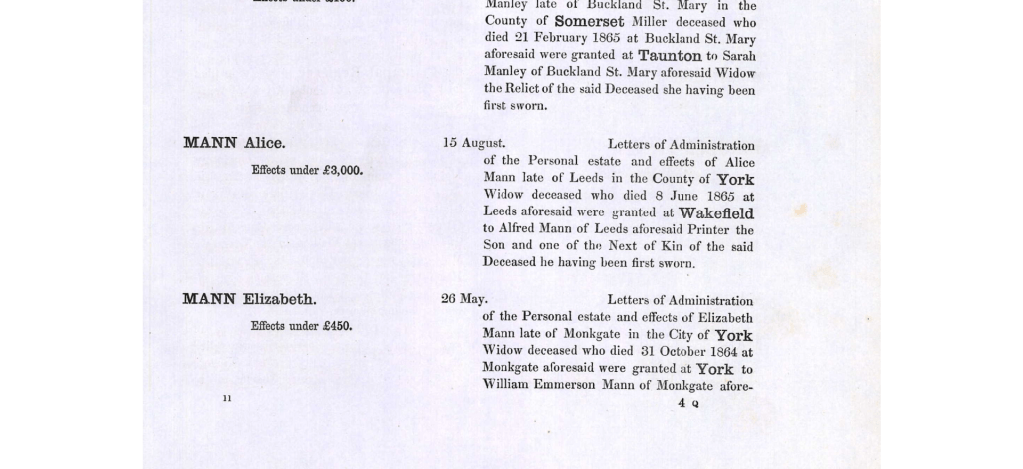

The only other facts are that she died on June 8, 1865, and left an estate worth less than £3000. It was administered by her son Alfred, who he carried on the business.

However, in 1876, a woman named Alice Burnett Mann married John Temple.

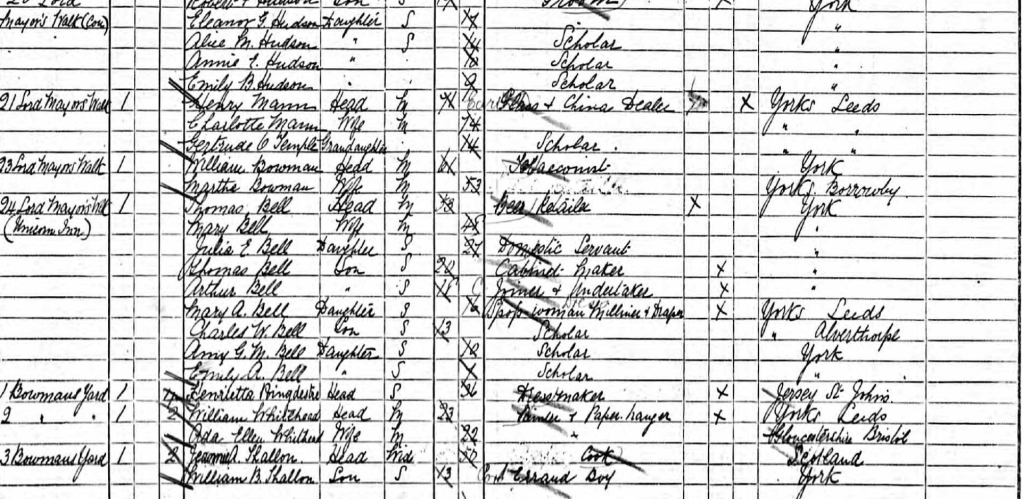

Who was Alice Bruneett Mann? One explanation is that in 1891, a child named Gertrude Temple was living in York with Henry Mann and his family. Gertrude was listed as Mann’s granddaughter. Henry Mann was one of the children of James and Alice Mann.

At a time when few women ran their own businesses, Alice kept hers going very successfully after her husband died. Equally rare, she was a woman involved in Radical politics in a period when it was a dangerous business, and raised a family on her own. A remarkable woman – one who deserves to be better-known than she is.

To finish, a reminder that Brass Lives is now out in hardback in the UK, and ready for you to buy or borrow from a library (ask your library – they’ll order it). The ebook will be available worldwide from August 1, and the hardback from September 7.

Some information for this piece came from posting to the Secret Libray website and David Thornton’s essential (to me) Leeds: A Biographical Dictionary. I’m grateful.