I had the pleasure of talking to a University of the Third Age group yesterday. I talked about my different series of books, including the importance of the old Victoria pub at the bottom of Roundhay Road (for anyone who doesn’t know: in my Victorian books it’s owned by Annabelle, the wife of the main character, Detective Inspector Tom Harper). From the 1920s to the 1940s it was actually run by my great-grandfather, and my father, who lived in Cross Green, used to go there regularly. Up where the family lived he could play piano for as long as he wanted, which was bliss to him.

After the talk a woman came up and told me she’d grown up on Manor Street, which is right by the Victoria in Sheepscar. Nowadays most of the area is builders’ merchants or light industry, but in those days it was streets of back-to-back housing. Except, she reminded me, the rhubarb fields. My father had mentioned them, although they’re hard to image when you go by on the bus now. He said they were part of the Victoria’s garden, but perhaps he misremembered (or I did). Maybe it was a proper rhubarb farm that belong to someone; I don’t know. After all, Leeds nudges against the famous Rhubarb Triangle.

It set me to wondering how many empty spaces within Leeds were cultivated. Not the Dig for victory campaign of World War II or the austerity years that followed, but long before that. Back-to-backs and terraced houses didn’t have anywhere to grow food. The allotment system as we know it today really started in the 19th century. The intention was to have plots for those without gardens, where they could grow food. A grand idea (I have an allotment myself), but there weren’t enough for everyone. Inevitably there was waste ground, and almost certainly people used it, just as people almost certainly kept pigs. There are records of the Irish on the Bank doing that in the first half of the 19th century – in their houses – and think of the film A Private Function.

Unofficial urban agriculture was almost certainly thriving. For some it was probably the only way to ensure their families received an adequate diet. Remember, too, that from the late 1700s there was a constant movement of people from the countryside to Leeds in search of work. These people and their children would have been used to growing things and many would have sought out spaces where they could do just that.

I’d be very interested to hear stories and memories of empty spaces in Leeds that were put to this kind of use. Please send them, or if you know of any articles/books relating to this, let me know. Perhaps we can put together a map of sorts.

The photo is courtesy of Leodis. It shows Sheepscar Sctreet with the large Appleyard garage. At the corner of Roundhay Road (towards the top left) you can see the Victoria pub proudly wearing its Tetley sign. The space behind the garage, and probably much of the area where it was built, would probably have been rhubarb fields.

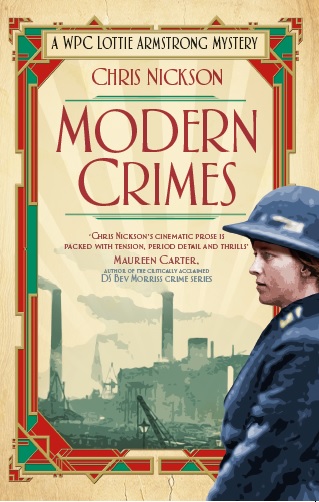

I’m sure you’re sick of me telling you, but…yes, I have a new book out, set in Leeds in the 1920s. A crime novel based on the first policewomen here. It’s called Modern Crimes, and Lottie Armstrong is front and centre. You might like it (and the ebook is very cheap).