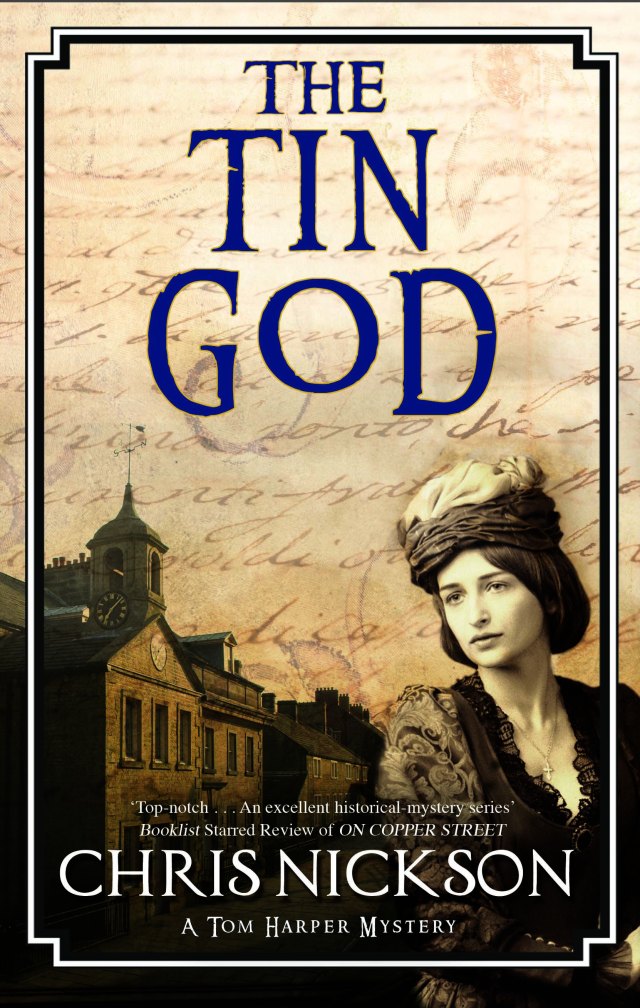

A couple of things have surprised me about The Tin God. Of course, I’m over the moon about the reviews it’s being receiving, far better than I could ever have expected.

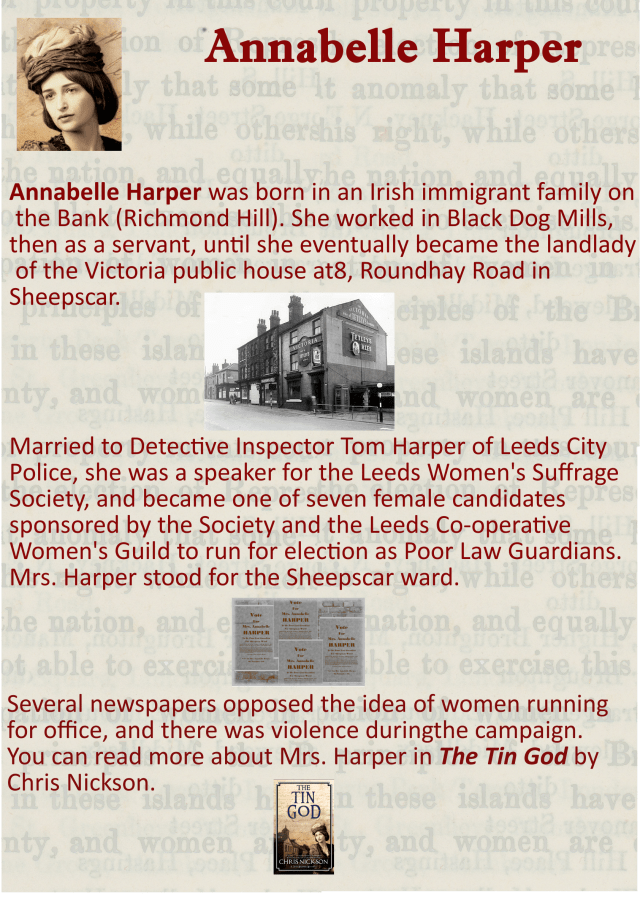

I set out to write a crime novel, a continuation of the Tom Harper series. And really, that’s what I did. But what people seem to see as the heart of the book is Annabelle’s fight to be elected as a Poor Law Guardian. That astonished me, but also gladdened my heart. It’s important, it’s vital, and it means, perhaps, that I’ve written something that reaches out beyond genre to deal with something bigger. As a writer, I don’t think you can ever aim to do that. If it happens, it’s serendipity.

The book has also changed me a little, made me more aware, more vocal on issues. And since I completed it, I’ve been assisting the curator of an exhibition called The Vote Before The Vote, about the Leeds Victorian women who worked for equality and the Parliamentary franchise, perfectly apt for the centenary of some women receiving the vote. Most of these figures are unknown, written out of suffrage history, and they deserve so much more than that. The exhibition runs for the month of May in Room 700 at Leeds Central Library, and there will be a website with all the information.

I’m very, very proud to be involved with this. I feel I’m contributing something to the history of my city. Happy, too, as the official launch for The Tin God takes place during the exhibition. And especially because Annabelle has her own board there as part of it all, melding fact and fiction. Emblematic of the working-class women who were involved in the long struggle. She’s become a part of history in a very tangible way, and I suspect that somewhere, she’s beaming with pride, although she’d never admit it.

On that note, I’ll give you a little from one of her election speeches, and hope it makes you want to buy the book. If you’re anywhere close to Leeds on Saturday, May 5, between 1-2 pm, come to the launch. There may well be more than you expect – and you’ll have the opportunity to see an important exhibition.

This takes place after someone has set fire to a hall when Annabelle is set to give a speech. Instead, she addresses the crowd out on the street.

‘This happened because someone is scared of women. Not just as Poor Law Guardians or on School Boards. He’s afraid of women. Frightened of half the population. What is there to worry him? Do you know? Because I’m blowed if I do. Just three years ago there were fewer than two hundred women as Poor Law Guardians in the whole of England. Two hundred out of a total of thirty thousand. It’s not exactly taking this over, is it? We want to increase that number here. People believe we should. Important people. The Archbishop of Canterbury, no less, thinks there should be more of us. I’ll tell you what the Secretary of State for India said: “No Board of Guardians is properly constituted when it is composed entirely of men. Having regard to the fact that so large a proportion of the population of our workhouses are women and children, it seems vital to me that women should take their part in Poor Law administration.” Even the men at the top of government and the church think we belong. The one who set fire to this place – to your hall – he’s swimming against history. Women are running for the offices they can hold, and some of them are going to be elected. If not this time, then next, or the one after. We’ve started and we’re not going to stop. That tide he’s swimming against, it’s going to drown him.’ Harper watched as she looked around the faces, her breath steaming in the air. She was smiling. ‘I’ll tell you something else. You vote for me, and you can help send him packing. More importantly, you’ll be electing someone who wants to help the poor, not punish them. You there, John Winters, Frank Hepworth, Catherine Simms. You all know me. You know where I live. Maybe the Temperance people might not like the landlady of a public house holding office. Yes,’ she told them, ‘I’ve heard that grumble. But you know that when I start something, I do it properly.’ She paused and drew in a breath, straightening her back so she seemed taller. ‘You’re ratepayers. You can vote. I’m asking you to put your X next to my name. Thank you.’

And remember. vote for Annabelle Harper!