Well, a part of one, anyway. The first scene came to me as I was walking, and I needed to write it, to get it out of my head. Then another scene came, and a third…quite what it’s going to be – or if it’s going to be anything at all – remains to be seen.

I’ve tried without success to write something set in Leeds in the 1960s. This might go the way of all the other attempts. Or perhaps it might click. But I’d honestly appreciate your reaction to it.

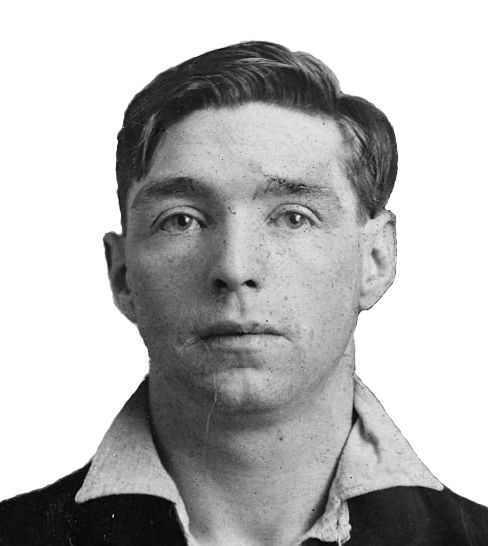

Picture courtesy of Leodis.

One

Leeds, April 1966

‘I’ll tell you what,’ Clarky began then took a sip of the beer. He was three pints and two Scotches into the evening, right around the time his tongue usually loosened.

Davy Wilson shook a Gold Leaf from a packet of ten and lit it. They were drinking in the City of Mabgate pub. Just a few hundred yards from Millgarth police station, but the coppers didn’t come in here. Except Detective Constable Robert Clark.

‘I’ll tell you what,’ he said again. Voice steady. It would take another two of three pints before he started to slur his words. Then the landlord would gently send him on his way home, up the hill to Lincoln Green.

‘What?’ Davy asked. Friday evening and across Leeds the mood would be rising. People putting on their best clothes. New dresses, suits from Burton’s. Knotting the tie just right. Some already out drinking, preparing for a night in the dancehalls and discotheques. Not him; another half hour and he’d be on his way home. But first he wanted to hear what Clarky had to say. When you worked for an enquiry agent, a copper’s information was like gold.

Sometimes gold, anyway. More often it was just shit. Still, no knowing when a nugget would show itself. Worth paying for a pint and a small measure Scotch. The cheap stuff; Clarky would never taste the difference.

‘You know George Hathaway?’

‘Georgie Porgie?’ Nobody would ever call him that to his face. He was big, as protruding belly, one of the most violent men in town, with a temper that could arrive from nowhere, like the flick of a switch. A criminal, running half the money lending and prostitution in town. And dangerous; there were rumours he’d made a couple of enemies disappear. But smart enough never to be caught, and enough policemen on his payroll to be certain he’d stay free.

‘Talk is he’s planning something big.’

‘Any idea what?’ He tried to make the question casual. It was business for the rozzers, not someone like him. His work was security. A different, safer world. Still, he was curious. Something useful might slip out.

‘No. But he has a pair of councillors in his pocket and I hear they’ve had full wallets lately.’ He took another sip. ‘Same with my Superintendent. He rolled up the other day in a Wolseley. Brand new, a 16/60.’

They didn’t come cheap, even with the kind of discount a dealer would give the police. Hathway, a pair of councillors and Superintendent Witham. Davy filed it away in his mind. Counted out three shillings and placed them on the bar before he stood and patted Clarky on the shoulder.

‘Have yourself another on me.’

Dickie Parsons studied himself in the bathroom mirror, pushing his fringe up a little. It wouldn’t last long, but he wanted to look perfect when he left the house. The suit was just right, three-button, two vents at the back, slim fitting, creases like knives on the trousers. A blue knitted tie.

In the hall he pulled his good overcoat from the stand and shouted bye to his parents. They’d be in bed long before he was home. He had work tomorrow morning, always a half day on Saturday, but he was twenty years old. Who wanted to stay at home and watch the telly on a Friday night? Plenty of time for that when he was old.

At the end of the drive, he stopped to light a cigarette. He’d been paid in the afternoon and he had some money in his pocket. Even after paying room and board to his mam and setting a little aside for a holiday, maybe a car or a motorbike, there was still plenty left for the weekend.

Rod and Jimmy were at the bus stop on Foundry Lane. They’d all been at school together, left as soon as they were fifteen. Jimmy had landed on his feet, an apprentice with an engineering company, with prospects for the future. Rod was a big lad with strong shoulders, content to carry hods full of bricks on the building sites. Dickie, though, he had a touch with engines, working at a garage in Cross Green, on decent money and learning. Always learning. Anything with a motor, he could repair it.

They had a laugh about work. But nights out were serious business. A few pints and over to the Mecca, see if there were any birds. They’d start at the Market Tavern, just up from the bus station, then across Vicar Lane for a couple more in the Robin Hood for going on to County Arcade and start dancing.

Dickie was beginning to feel the weekend, a little buzz in his body, like that time someone gave him a Purple Heart. The week before he’d noticed a lass at the Mecca. Short skirt, long legs, short dark hair and big, wide eyes like Twiggy. Mandy, she’d told him as they talked for a couple of minutes before her friends dragged her away to the bus.

‘Maybe see you next Friday,’ he told her. He’d keep his eyes open; there’d been a promise in her smile.

Dickie stood by the bar in the Robin Hood, the air thick with cigarette smoke and talk. He chuckled to himself as he saw the daft little World Cup Willie gonk someone had put on top of the optics. Still, it was only a few weeks until the matches started, and he was looking forward to the football. He was in a good mood, ready to have a little fun, when somebody pushed into him, hard enough to make him lurch forward and spill his beer. The first thing he did was look down. The bottoms of his trousers were safe, just a few drops. Most of it splashed onto his Chelsea boots. A flash of annoyance. He’d only bought them the weekend before.

Dickie turned around. ‘What the hell do you think you’re doing?’

The man was fat, a glass of Scotch in his thick hand. A pair of hard cases stood beside him.

‘Sorry, lad,’ he said. ‘No damage done, eh?’

‘All over my bloody shoes.’ Suddenly Rod and Jimmy were there.

‘I said sorry, all right? Let it go.’

He’d had just enough to drink to show a little bravado. ‘You can buy me another pint.’

He saw something change in the fat man’s face. In an instant it grew hard and dangerous.

‘I said sorry. I’m not buying you owt. Leave it while you can.’

‘Least you can do is stand him another,’ Jimmy said.

The big man turned his head a little. ‘I’d shut up if I were you.’

‘What do you want to do, boss?’ one of the hard men asked.

‘Nothing.’ He was staring at Dickie. ‘These boys were just leaving.’ He had a smile that looked like a curse. ‘It’s probably past their bedtime, anyway. Let them go home to mummy and cocoa.’

It was Rod who put a hand on Dickie’s shoulder.

‘Come on, mate. It’s not worth it. We’ve got better things to do.’

Dickie stood his ground, staring at the fat man for five seconds.

‘Yeah,’ he agreed finally. ‘Let’s go.’ As he pulled the door open, he looked back. The fat man was still watching him, amused now.

‘Pillock,’ he shouted.

Then they were out on the street. Only a few yards to the County Arcade and the Mecca where the night could really begin. But he heard the footsteps behind them. He glanced and the others.

You couldn’t run for it. You didn’t do that. You stood your ground even if you knew you couldn’t win.

Then Rod and Jimmy were on the floor, the hard men kicking them like they were playing at Elland Road. Dickie was facing the fat man.

‘You need to learn some respect, boy.’ He grabbed Dickie’s lapels, pulled him close and brought his head down hard. Dickie felt his nose explode. Pain and a sudden gush of blood. He opened his mouth to cry out. Then the fist caught him on the chin and he was flying back on to the pavement.

Two

Leeds, June 1966

‘Do you remember that assault on Boar Lane back in April? A Friday night, three lads in hospital. One of them in a coma.’

Davy Wilson lifted his head. Charlie Hooper was staring out of a dirty window, gazing at the blackened stone of Mill Hill Chapel on the other side of Lower Basinghall Street.

‘I remember seeing it in the paper. Why?’

‘He came out of the coma yesterday. They’re not sure if he has brain damage.’

Davy waited. Charlie wasn’t the type to bring something up out of the blue and then leave it hanging there. He was usually decisive, mind sparking. Today he seemed…distracted. Sad. Not like him at all. There had to be more

Hooper had served in Military Intelligence during the war, left with a good record, came back to Leeds and started the business. He had the kind of face nobody remembered, a real asset for this line of work. Sharp enough to look ahead and see the divorce laws were likely to change soon. That market would vanish. He’d begun to push the industrial security side of their work to keep them ahead of the competition That was Davy’s field. Aged eighteen, three A-levels behind him, he’d started worked for a company making burglar alarms and sense the possibilities. Three years of that, learning the electronics and how to set everything up, he’d done his research on enquiry agents and gone to see Hooper. Another trade to learn, how to work on the street and with the police while he built up contacts with businesses and Charlie used the friends he’d developed. It was starting to pay off for both of them, and Davy was still only twenty-six.

‘Poor lad,’ he said. What else was there?

Charlie nodded and ground out his cigarette in the ashtray. He was in his fifties, white hair, a bald spot on the crown of his head. He smoked too much, starting to go to seed: nicotine stains, jowly, belly ending over the top of his trousers. ‘Happened on a Friday evening right in the middle of town.’ He spoke quietly, thoughtfully; he could have been talking to himself. ‘A couple of witnesses gave statements to the police. The way I heard things, they went back later and changed their minds.’ He raised his eyebrows. ‘Nobody on the force pushed them.’

‘It happens,’ Davy said. ‘We both know that. Someone put the fix in.’

‘Yes,’ Charlie agreed. ‘Dickie, the one in the coma, he’s my cousin’s boy.’ He turned his head to stare at Davy. ‘She asked if we could do something.’

‘What did you tell her?’

‘I rang a couple of coppers I know. They’re not saying a word.’ A pause, no more than a moment, but it felt like a lifetime. ‘You drink with that detective out of Millgarth, don’t you?’

‘Sometimes.’ He knew what was coming.

‘Can you ask him? See what he knows?’

‘I can try.’ Tomorrow was Friday. Come evening, Clarky would probably be in the pub.

‘I’d appreciate it.’ A small, wan smile. ‘Dickie’s a good kid. We’re going to have to wait and see how he goes along. Meanwhile…’

‘Yes.’

While you’re here, just a reminder that this book is still pretty new, very dark and (I think) pretty damn good. You might like to try it.