Next April sees the publication of No Precious Truth, the first in a series featuring Woman Police Sergeant Cathy Marsden, who’s part of the Special Investigation Branch’s squad in Leeds.

But how did a woman serving in Leeds City Police end up there?

Here’s Cathy’s story. It’s the first in a series of posts about Leeds in World War Two to prepare you for next year. A little taste, if you will.

September, 1940

‘Sorry if I’m late, ma’am. I came as soon as I knew you were looking for me.’

‘I thought someone would find you soon enough.’ Inspector Harding sat behind her desk, all her papers carefully squared and ordered. After fifteen years of steady work on the force, she’d risen to be in charge of the women police constables.

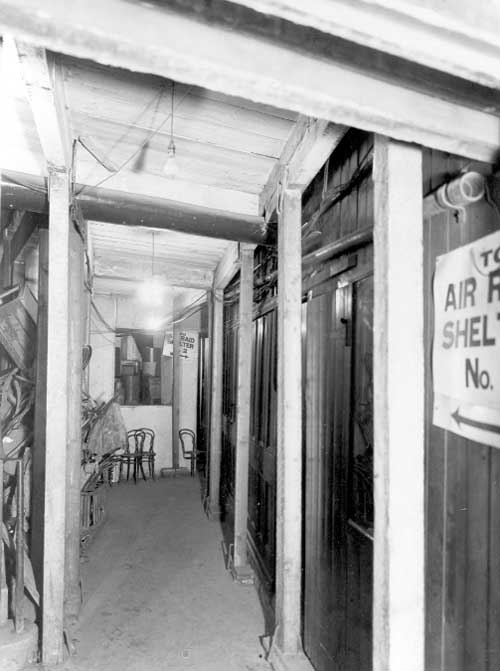

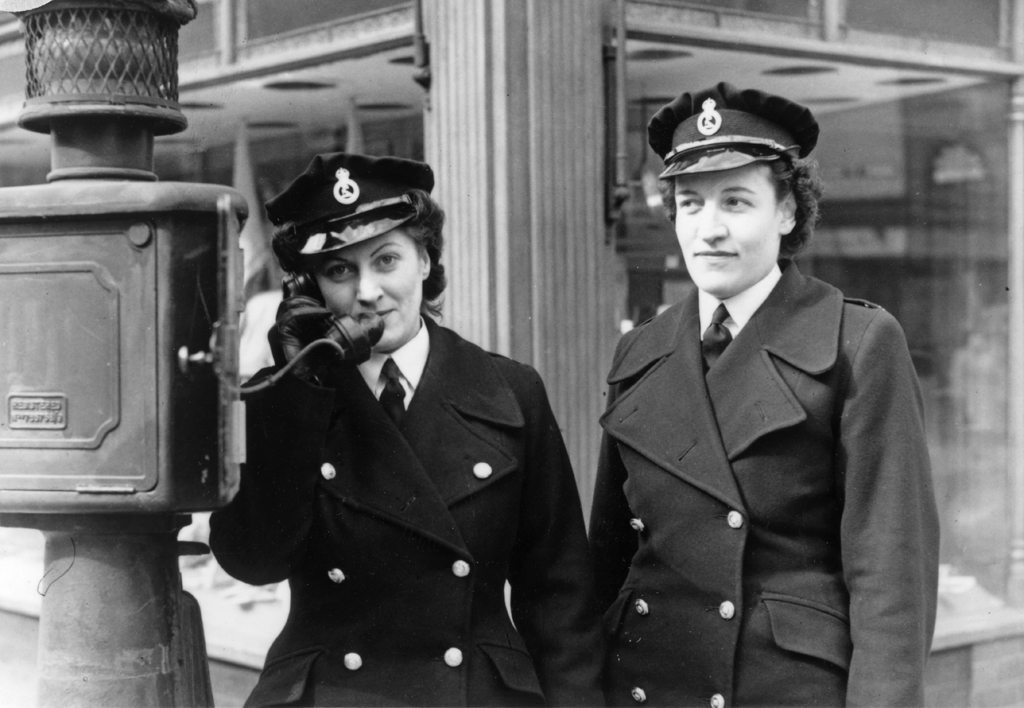

From Flickr

‘Have I done something wrong, ma’am?’ The question had gnawed at her as she hurried up Briggate and the Headrow. She couldn’t imagine what, but…

Harding couldn’t help herself; she had to laugh. ‘No, Sergeant. It’s nothing like that. Sit down.’

‘Ma’am?’ Harding was always friendly, but one for order and boundaries.

‘Please, take a seat, Sergeant.’

Once Cathy was perched on the edge of her chair, the inspector began.

‘I’ve been watching you these last few months. I don’t know what’s changed, but you don’t look happy in the job.’

‘Ma’am?’ she said again. Had it been that obvious? And what was so urgent about a heart-to-heart? Something like this could wait until the end of shift.

‘Please, Marsden. I wasn’t born last week. It’s been obvious.’

‘If my work isn’t up to snuff-’

‘You work is as good as it’s always been. You been on the force for six years?’

‘Yes, ma’am.’ Where was the woman going with this?

‘Something’s shifted. It seemed as if it happened when we received those men who’d survived Dunkirk.’

That was all it took. She hadn’t intended to say much, but once she began, it all flooded out.

‘Well,’ Harding said in an easy voice when Cathy finished, ‘I think what we do is important. But I can understand how you feel.’ She took a cigarette case from her breast pocket and offer one to Cathy before lighting her own and blowing a think plume of smoke to the ceiling. ‘Tell me, if I can offer you something different, some far from your routine that might change things in the country a little, what would you say?’

‘I don’t know.’ Her mind was racing. She didn’t understand what the inspector meant. ‘What is it, ma’am?’

‘How would you fancy working in plain clothes for a little while?’

‘Me?’ she asked in disbelief. There were only eight women police officers in Leeds, and not a single one of them was in CID. Never had been, and never would be, if the top brass had their way. That was strictly male territory. A few forces had women detectives, but it would be a cold day in hell before it happened here. As it was, twenty years after the first policewoman was appointed in Leeds, they were still barely tolerated in uniform. ‘How?’

‘Have you ever heard of an outfit called the SIB? The Special Investigation Branch?’

‘No, ma’am.’ All her thoughts was spinning. After the way CID had treated her yesterday, she was suspicious. What would these SIB people expect her to be, the tea girl?

‘I’m not surprised. They only started up in the spring. They’re more or less the military police version of CID.’ She paused and gave a short, reassuring smile. ‘Different, though. They investigate crimes involving soldiers.’ Harding held up her finger before Cathy could open her mouth. ‘They have a big operation that’s just begun here. The head of their squad, Sergeant Faulkner, came to see me first thing about seconding a WPC to them for it. They need someone who knows Leeds very well. It might be exactly what you need.’

‘Why a policewoman, ma’am?’

‘Someone who’s used to disciplined thinking and can obey orders. Well trained.’

That made a curious kind of sense. But: ‘Why me?’

Harding gave a kindly smile. ‘Eighteen months ago you were promoted to sergeant. I fought for that because you’re the best I have. You’re a natural leader. The others ask you questions, they listen to you. They look up to you.’ Cathy blushed, feeling the heat rise on her face. ‘You’re very observant. You have a real way with people, too. You put them at ease. They open up when you talk to them. I don’t want you to leave the police. If I second you to SIB for their operation, I believe you’ll come back refreshed and raring to go. If not, then leave the police and find something else. Does that sound fair?’

Cathy stayed silent for a long time as fears and hopes chased each other around her head.

‘Do you honestly think I can do it, Ma’am?’

Another smile, this one glowing with satisfaction. ‘My reputation is one the line, Marsden. If I wasn’t certain, I’d never have put you forward for it.’

She scribbled an address on a scrap of paper and pushed it across the desk. ‘Go here and talk to Sergeant Faulkner. He’s expecting you. The SIB have their own office, separate from the army and us.’

Cathy tucked it in her uniform pocket, stood and saluted. ‘Yes, ma’am.’

‘There’s one condition, and I made this very clear to Sergeant Faulkner: if I need you back for something, the police take precedence. You understand?’

‘Yes, ma’am. And thank you.’

‘Go and show them what you’re made of, Sergeant.’