Continuing these 10 years of publishing crime novels set in Leeds, I’m moving back in time a little to revisit Detective Sergeant Urban Raven, the main character in The Dead on Leave.

That book took place in 1936. We’ve moved on a bit, to 1939, with the shadow of war hanging very dark over Britain.

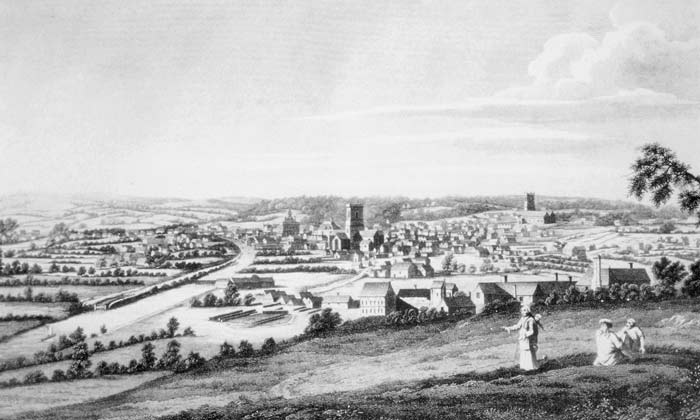

Leeds, April 1939

‘I’m coming in,’ Raven shouted. ‘Just me, I’m a policeman and I’m not armed. No need to take a pot shot at me, all right?’

He waited, but there was no reply. He’d never really excepted one. He tapped the trilby down on his head, tightened the belt on his gaberdine mackintosh and took a deep breath. Nothing to worry about. The lad would be too scared to fire again, and he certainly wouldn’t dare fire at a copper.

He turned and looked at the other. Detective Inspector Mortimer and DC Noble standing behind the black Humber Super Snipe, and the three constables waiting for orders.

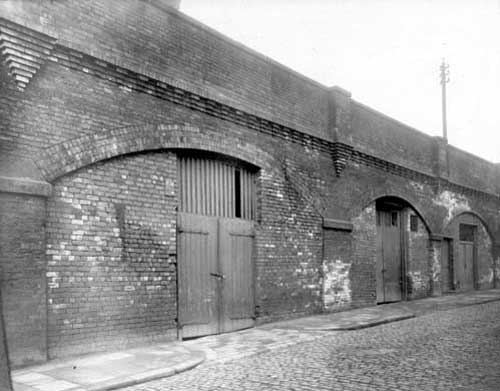

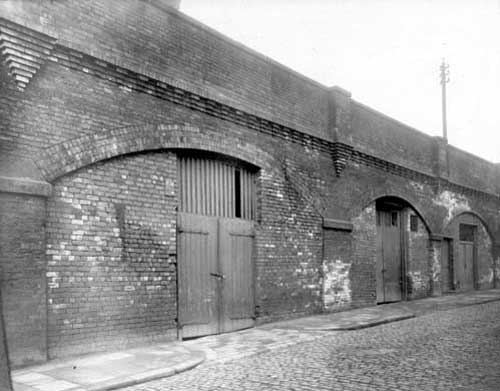

A deep breath and he began to walk across the cobbles. At the top of the embankment a train hurried by in a flurry of steam and smoke. Detective Sergeant Urban Raven put his hand on the doorknob of the workshop under the railway arch, paused for a fraction of a section, then turned it.

He stood, silhouetted by the daylight on Kirkgate.

The gun boomed.

The world was damp. It seemed to cling to him. Rain had fallen every day since the beginning of the month, sometimes heavy, sometimes no more than a mist. But it was always there. Everything seemed brown or grey in the city centre. People moved purposefully heads down. Nobody idled or stared and smiled.

Urban Raven didn’t mind. If they never looked, he’d be perfectly happy. His face bore the thick scars and shiny skin of plastic surgery. In France, October 1918, he’d been badly burned when a German shell exploded in a fuel dump. Two decades on and he was still all too aware of the effect he had, the way people glanced at him, then hurriedly turned their heads away. Sometimes he even imagined he saw disgust on his wife’s face. Or it might have been pity. Hard to tell which was worse. It seemed easier to think about work. There was always plenty to do.

War was coming. Chamberlain had claimed he brought them all peace in his time, but everyone knew the truth. All the young men on the police force would go into the services. Everything would fall on the shoulders of old-timers like him, on the policewomen and Specials. The only question was when the axe would fall. Soon, people agreed, soon; it seemed they were holding their breath.

Raven knew about some of the preparations, the amount of re-armament, civil servants preparing for a flood of army volunteers. He’d helped with checking the records on aliens around Leeds; come the declaration of hostilities and they’d quietly visit some of them and send them off to internment camps.

But right now, as he walked through Harehills, up Hovingham Avenue to Dorset Road, it all felt a long way off. It might never happen.

He rapped on the door of number seventeen, one more terraced house in a long row of them. Nobody answered. But someone was inside. He felt sure of it; he could feel them there, hiding away until he left.

Raven knocked once more, then went back down the street, glancing over his shoulder. No one had appeared. No twitch on the curtains to show he was being watched.

Easy enough to slip down the ginnel. The wall at the back of the yards was tall enough to hide him. He counted his way along, then placed his hand on the latch of the gate he wanted.

Even before he could press down, someone pulled it open and he was face-to-face with Bert Dawson, watching the man’s jaw drop in astonishment. Collywobbles, that was his nickname. The slightest thing and he’d start shaking with worry.

‘Fancy meeting you here,’ Raven said with a smile. ‘You’re just who I wanted to see.’

‘You should have come to the front door, Sergeant Raven. I was just off to the shop.’ But he was already shaking like an old man.

‘Happen I can save you the trip. We’ll have a cup of tea down at headquarters and you can tell me about those robberies you’ve been on lately. You made off with a nice little haul, by the sound of it.’

The CID office was upstairs in the Central Library, and Raven marched Dawson up the wide tiled steps.

‘You see, Collywobbles, you’re moving up in the world. Getting yourself charged in a place like this, not the local nick. You should be pleased.’

He’d just finished taking the statement when Mortimer popped his head round the door.

‘Have a uniform take him down to the bridewell.’

By the time he reached the office, men were already shrugging into their overcoats and pushing their hats over their eyes.

‘What is it?’

‘Wages robbery,’ Mortimer said. ‘Down at Hope Foundry. Two thieves and a driver. They had a sawn-off shotgun. Fired it. A couple of clerks were hit, one’s in bad shape. They got away, but they’re in a workshop in the railway arches on The Calls.’

‘Are we signing out any weapons?’ DC Noble asked.

‘Already done, lad. We have a trained marksman down there.’

Three of them in the plain black car, Mortimer driving. No bells ringing. Everything quiet. He weaved in and out of the traffic on the Headrow and Vicar Lane, halting by the police roadblock on Harper Street.

‘Are they all still in there?’ Raven asked the sergeant in charge.

‘Witnesses said one of them scarpered as soon as they pulled up. We’ve got a description and we’re hunting for him now. But the shooter’s still inside.

‘What do you want to do, sir?’ Raven asked Mortimer.

‘First of all we’re going to evacuate all those businesses other arches. We don’t want any civilians around if there are people with guns. Take care of it,’ he order the uniformed sergeant. ‘After that, about all we can do is tell them the police are here so they should come out and surrender.’ He lit a cigarette and shrugged. ‘It’s all rather like a gangster film, but I don’t see what choice we have.’

A train rattled along, gathering speed as it left the station and going east. Smuts of soot settled all around them.

‘Do we have any idea how much they took?’

‘Well over a thousand,’ Mortimer answered as he blew out smoke. ‘Hardly pocket money, is it?’ He glanced around. ‘The marksman is upstairs in the warehouse across the street. He’ll be ready if we need him.’

‘Let’s hope we don’t, sir.’ Raven stared at the door. Big and broad for a motor car to fit through. Made of corrugated iron, like the rest of the covering over the arch. Worn and rusted. A tiny window to let in a little light. A thought struck him. ‘Could we cut off their electricity? Do that and it’ll be pitch black in there.’

‘We will if they don’t surrender,’ Mortimer agreed. ‘We’ll get someone down here, just in case.’

A young constable ran up and spoke quietly to Noble. The man frowned.

‘One of the clerks who was shot at the foundry has died. A girl, not even twenty.’

‘They’ll hang for that.’

‘Tell them, sir?’

Mortimer shook his head. ‘Not until they’re out and we have the weapon. They won’t give up otherwise.’

The sergeant dashed up, face red from running. ‘All the other arches are empty, sir.’

Inspector Mortimer picked up a megaphone and began to speak. It made his voice ring around the street. They’d be able to hear him clearly in the arch. A simple offer, a promise of fair treatment if they gave themselves up.

The silence hung heavy when he finished. Nothing from inside.

‘Electricity, sir?’ Raven said after they’d heard no sound for two full minutes.

‘Yes,’ Mortimer replied. He kept his gaze on the arch, finishing one cigarette and replacing it immediately with another.

It didn’t take long. The man was up the pole and back down again in the blink of an eye.

‘It’ll be like the dead of night in there for them,’ he said as he hitched up his leather tool belt and pulled down his cap. ‘You need me for owt else?’

Over the next two hours, Mortimer used the megaphone twice more. But there never any answer from inside.

Raven began to walk, flowing the pavement around the embankment where the old gravestones from the Parish Church burial ground cover the grass. No way out on the other wide. The killers were trapped in there. But not in any hurry to come out.

‘I don’t know about you, sir, but I don’t want to spend the rest of the day here,’ he said.

‘Any good ideas?’ Mortimer asked.

‘March in and drag them out.’

The inspector shook his head. ‘They have a gun and not much to lose right now.’

‘We can take go in. It might take them by surprise.’ He glanced across the street to the marksman waiting in the window, his rifle tight against his shoulder. ‘Just make sure he’s ready.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘What’s the choice, sir?’ Raven said. ‘Go in mob-handed? We risk losing more men that way. If we try to wait them out, they’ll be firing when they open the door. And God knows when that might be.’

‘I can’t order you to do it, Sergeant.’

‘I know, sir. I’m volunteering.’

If they killed him, what would that matter? No more looking at the face in the mirror every morning. No more thinking that his wife couldn’t stand to see him. She’d be able to find herself someone who looked normal.

He liked his job, he enjoyed being a detective. But if this was it…at least he wouldn’t pass the young lads on the street and wonder which of them might end up like him after the next war. And it was coming soon enough…

Mortimer cocked his head, as if he could read all the thoughts in Raven’s head.

‘If that’s what you want.’

‘It is, sir.’

A deep breath and he began to walk across the cobbles. A train crossed overhead in a flurry of steam and smoke. Detective Sergeant Urban Raven put his hand on the doorknob of the workshop under the railway arch, paused for a fraction of a section, then turned it.

He stood, silhouetted by the light on Kirkgate.

The gun boomed.

A pause, then it fired again.

The smell of cordite. Thick smoke that made him cough. His ears rang; he couldn’t hear a thing.

But he wasn’t hit. No wounds at all.

As the air began to clear, he could see them. A pair of young men in cheap, flashy suits, gaudy Prince of Wales checks. They were lying on the floor, sprawled on their back and staring into eternity. They shotgun lay between them.

Christ, he thought. He’d expected the worst, but not that.

Christ.

‘It’s me,’ he called. ‘I’m coming out, Everything’s safe in here.’

The Dead on Leave is available in paperback and as an ebook.