I’m trying something new, set in Leeds of course, this time in 1862 (although the section coming up in 1858, to confuse you). It’s a little different – I have about 20,000 written. This is the opening – I really like the characters – but I’d honestly love to know what you think.

Meet Virginia Cooper. Her husband will be along shortly

‘Mrs Cooper,’ the chief constable said, ‘allow me to be blunt.’

Finally, she thought, but made sure her face showed nothing. For the last five minutes he’d been going round the houses, offering hesitant comments about the weather, the roads, anything but the reason she was here.

‘Of course, sir.’

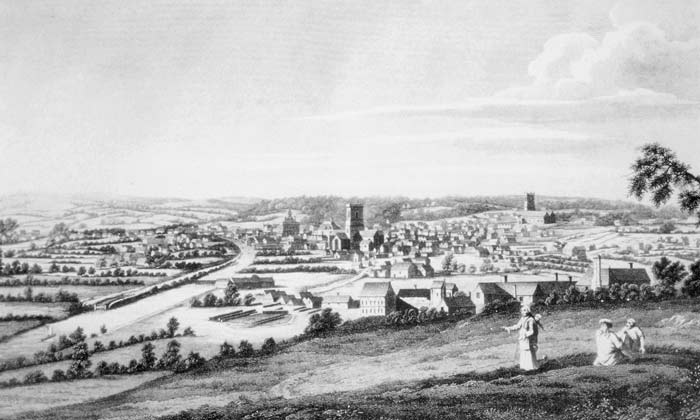

Virginia had arrived at the town hall half an hour earlier, nine o’clock on the dot, stomach fluttering as she patted the stone lions on the steps for luck. Just a month before she’d been a speck in the crowd that had gathered along the road to watch Queen Victoria arrive in her carriage and open the building. Now she was inside, and the splendour of it all, with its polished marble and granite, captured her breath for a second.

She was in her finery, the dress and she and daughter Ellie had sewn at the start of spring, a pale, spotted muslin with false sleeves, embroidered belt and a tiered skirt that cascaded to the ground, copied from a London magazine, all topped by a hat prettily decorated with flowers and ribbons. The button boots on her feet were polished to a brilliant shine. She’d been up early, fussing over every little detail, desperate to make a strong impression. As she sat across from him, with Her Majesty’s portrait gazing down from the wall, she felt up to the mark, pushing down the nerves she’d had before she met Chief Constable Broadbent.

He was a fastidious, exact man. His appearance made that obvious, with a well-cut suit, a high, crisp collar and neat tie held in place by a small gold pin. Pale, soft skin, a double chin, and luxurious combed mutton-chop sideboards that spread across his cheeks. Long, thin fingers with clean nails that kept toying with a pen to try and hide his awkwardness. An outstanding policeman, her husband had told her; the men would follow him anywhere. A bachelor, she knew that, too; obviously hesitant and uncomfortable around women. Seeing that made her feel easier.

‘I’ll ask you plainly: would you be interested in working with the police force, Mrs Cooper? Your husband has, hmm, praised you as a woman of intelligence and rare perception.’

‘He’s very generous to say so, sir.’ Woe betide him if he’d said anything less, she thought. ‘What would you require me to do?’

No skivvying, no ironing shirts or cleaning. She’d made that plain to Rob when he first raised the idea two evenings before. He’d shaken his head and laughed, then put his arm around her shoulders. ‘I wouldn’t dare. No, this is something to exercise that brain of yours.’

She narrowed her eyes. ‘What do you mean? Something like your duties?’ Robert Cooper was the inspector of detectives in Leeds police, with a sergeant and two men in plain clothes under his command.

Virginia thought she’d kept her restlessness well hidden. The wish for something more in her life. She didn’t know what, she couldn’t name it, but it was there inside her.

But he’d seen, and he’d been sharp enough to come up with this, something that might settle the ache inside. But never in a million years would she have imagined an involvement with the police as the answer. How could she? Female detectives simply didn’t exist.

‘A little similar,’ he allowed. ‘Doing things that a man can’t manage so easily.’

Her pulse had begun to beat faster. But…

‘Does it pay?’ she asked sharply. The job sounded intriguing. But if the police wanted a woman, they could pay her a wage.

He nodded. ‘If things go well, it could become fairly regular paid employment.’

If things go well. Virginia saw that satisfied look in his eye; he knew he’d piqued her curiosity.

‘I’ve been, hmm, considering the idea of a woman to work with our detective police,’ the chief constable continued. ‘A couple of other forces have enjoyed success using women in, hmm, certain situations. Often the wives of policemen. They deal with females who are breaking the law, for instance, searching them when they’re arrested or following them around town.’

‘I understand, sir,’ she said, fingers tight around the reticule in her lap, lips pressed together, trying to keep the hope out of her voice.

‘It will require discretion and a certain amount of skill,’ he said. ‘A person of a certain maturity. More than that, Mrs Cooper, you have to understand, any arrangement must remain, hmm, completely unofficial. You won’t have the power to arrest anyone, of course, and you can’t tell people what you do. I’m sure you can see that the majority in Leeds – throughout England, for that matter – would never, hmm, condone the idea of a policewoman.’ He offered her a fleeting, earnest smile. ‘I can’t imagine her majesty would approve, either.’

‘I’m sure she wouldn’t, sir.’ Her heart was pounding. The job felt close enough to taste.

Then the questions about herself. Did she have children? Two, from her first marriage. A grown son named Tom, now an assistant manager at Queen’s Mill in Castleford, and a daughter aged sixteen, Eleanor, living at home and apprenticed to a dressmaker. There’d been one more, the very first. He’d died of diphtheria before his second birthday.

How did she feel about a wife working? When it was something like this, it was a service to the town, she replied and looked at him. Didn’t he feel that way?

Broadbent reddened slightly and turned away for a second.

A few more things, but she’d been reading men’s expressions for most of her forty-five years. He was satisfied, he’d made up his mind. The chief constable gathered his papers together, tapped them into a neat pile and took a breath.

‘Mrs Cooper, if you’re willing, I would like to have you work with Leeds police. One job to begin, a, hmm, trial, as it were. Then possibly more to follow. We’d pay you by the case to start.’

‘Thank you, sir. I’d be very pleased with that.’ She didn’t try to hide her broad smile. A female detective. The eagerness overflowed in her voice. ‘Do you have something in mind to begin?’

‘I do,’ he said. He steepled his forearms on the desk and delicately rested his chin on his fingertips, eyes down to avoid her stare. ‘I don’t know if you’re aware of it, but a pair of fortune tellers arrived in town at the end of last week.’

‘Yes, sir.’ It had been common gossip at the covered market on Kirkgate. They’d come and set up in a house on Trafalgar Street in the Leylands.

‘I’d like you to make an appointment and, hmm, have your fortune told. A woman will raise no suspicion. Make a note of everything, and report back here afterwards. Fortune telling is an offence under the Vagrancy Act, you see. We’ll take care of the prosecution.’ His face clouded. ‘You realise that the, hmm, the nature of your work must largely stay in the shadows, Mrs Cooper. You’d only step out of them if you have to give evidence in court.’ He cocked his head. ‘Would you be comfortable doing that?’

For a moment, Virginia felt a panic rise in her chest. Rob had never mentioned anything about that. He’d probably never thought about it; facing judges and counsel was second nature to him. But she only needed a moment to make up her mind: she didn’t know if she could do this work, but she was desperate to try, to see if it could provide what was missing.

‘Yes, sir.’ Her voice was firm. ‘I would be willing to do that.’

‘Excellent.’ He smiled, a real look of warmth on his face. ‘Detective Sergeant Bell will give you the details.’ Broadbent extended his hand. ‘Welcome, Mrs Cooper.’

Four years had gone by since then. She’d learned how to spot frauds, been scratched and bruised as she searched female prisoners, and trailed pickpockets all over Leeds. She’d seen heartbreaks and horrors that returned to haunt her through the nights. Tried to comfort a young woman whose drunken husband had beaten her halfway to death simply because she answered him back. Heard the anguish of a woman whose man had just murdered her young child. She’d spent five hours in a dark, muddy cellar along Marsh Lane with a female killer, while water leaked through the wall to lap over her ankles, constantly alert in case the woman tried to attack her.

She’d watched the harm people did to each other, more of it than she could ever have conceived. Known their fears and violence and learned to develop a shell to protect herself. Along the way, she’d come to understand that she had a gift for this. Rob must have seen that in her. But now she understood why he never wanted to discuss the job when he came home; it kept his family safe from the demons that lived inside him.

While silent, unspoken, she kept her own well of sorrows hidden.