It’s definitely spring out there. The kids are enjoying their holidays, the weather is growing balmier. I’ve been able to get things planted at my allotment, and it’s beginning to take shape for the season.

But life wouldn’t be right if I wasn’t writing, and I have my head deep into what I hope will become the sixth Tom Harper novel, although Annabelle proves to be a very big part of this one. Now I just have to hope that my publisher wants it.

This extract is fairly lengthy and is still in a fairly raw state, so I hope you’ll bear with me on that. More importantly, I hope you like it. Please, seriously, tell me what you think, okay?

Late September, 1897

Tom Harper stared in the mirror.

‘What do you think?’ he asked doubtfully.

He felt ridiculous in a swallowtail coat and stiff, starched shirt. But the invitation had made it clear: this was an official dinner, formal dress required. The fourth time this year and the suit wasn’t any more comfortable than the first time he’d worn it. He’d never expected that rank would include parading round like a butler.

‘Let’s have a gander at you.’ Annabelle said and he turned for inspection. ‘Like a real police superintendent,’ she told him with a nod. ‘Just one thing.’ A few deft movements and she adjusted the bow tie. ‘Never met a man who could do a dicky bow properly. Now you’re the real dog’s dinner.’

She brought her face close to his. For a moment he expected a kiss. But her eyes narrowed and she whispered, ‘I’ve had another letter. Came in the second post. May Bolland’s had one, too.’

His face hardened. He’d expected some outrage when Annabelle announced she was running to be elected to the Board of Poor Law Guardians. A few comments. Plenty of objections. He was even willing to dismiss one anonymous, rambling letter as the work of a crank. But two of them? He couldn’t ignore that.

‘What did it say?’

She turned her head away. ‘What you’d expect.’

‘The same person?’ he asked and she nodded. ‘What did you do with it?’

‘I burned it.’ Her voice was tight.

‘What?’ He pulled back in disbelief. ‘It’s evidence.’

‘Little eyes,’ she hissed. ‘You know Mary’s reading has come on leaps and bounds since she started school. Safer out of the way.’

He breathed slowly, pushing down his anger. For a long time he said nothing. What could he do? It was dust now. Maybe Mrs. Bolland had kept hers; he’d send Ash round to see her in the morning.

‘Button me up and we’d better get a move on.’ Deftly, she changed the subject. ‘That hackney’s already been waiting for five minutes.’

Annabelle was wearing a new gown, dark blue silk, no bustle, high at the neck with lace trim and full leg-of-mutton sleeves, the pale silk shawl he’d bought her over her shoulders. Her hair was elaborately swept up and pinned. She was every bit as lovely as the first day he’d seen her.

There were calls and whistles as they walked through the Victoria pub downstairs. Her pub. She laughed and twirled around the room. He was happy to keep in the background, to try and slink out without being noticed. People didn’t dress like this in Sheepscar. They owned work clothes and a good suit for funerals; that was it.

‘What is this do, anyway?’ she asked as the cab jounced along North Street.

‘The Lord Mayor’s Fund,’ he replied. ‘Charity.’

The Mayor’s office had finally become the Lord Mayor’s office that summer, Leeds honoured by Queen Victoria to mark her Diamond Jubilee. Sixty years on the throne, Harper thought, going back long before he was a twinkle in anyone’s eye, before his parents had even met. There had been parties and civic events around the city all summer, and hardly any problems, as if everyone just wanted to celebrate the occasion with plenty of joy.

The Chief Constable had been pleased, and even happier when the crime figures came out: down everywhere. The biggest drop was in Harper’s division. God only knew why; he didn’t have an explanation. He’d praised his men then held his tongue, not wanting to tempt fate.

Annabelle’s elbow poked him in the ribs.

‘You’re miles away.’

‘Sorry.’

‘Is it a sit-down affair tonight?

‘Three courses, then the speeches.’

She groaned and he turned to smile at her.

‘We’re in for plenty more of these once you’re elected.’

‘If I’m elected,’ she warned. ‘Don’t be cocky.’

Seven women were standing to become Poor Law Guardians, their election costs paid by the Suffrage Society and the Women’s Co-op Guild. The campaign was no more than three days old, but already the Tories and the Liberals were deriding the women for trying to rise above their natural station. The Independent Labour Party had its eye on the posts, too, as stepping stones for their ambitious young men. And the newspapers had their knives out, pointedly advising people to vote for the gentlemen. He’d arrived home two days to find her pacing furiously around the living room, ready to spit fire, with the editorial in her hand.

‘Listen to this,’ Annabelle told him. ‘Apparently they think men “don’t possess the domestic embarrassments of women.” What does that mean? I could swing for the lot of them.’

She threw the paper on to a chair. But he could hear the hurt behind her words. It wasn’t going to be a fair fight.

The first letter arrived the same day. Second post, franked at the main post office in town, no signature or return address. It was a screed about how women should be guided by their husbands, live modestly and look to the welfare of their own families. Religious and condescending, everything written in a neat, practised hand. Senseless, Harper judged when he read it, but no real threat. All the women running for the Board had received one. He’d placed it in his desk drawer at Millgarth and forgotten about it. But another…that demanded attention.

‘Take a look at that,’ Harper said and tossed the letter across the desk. Inspector Ash raised an eyebrow as he read, then passed it on to Detective Sergeant Fowler.

‘Looks like he’s halfway round the bend, if you ask me, sir,’ Ash said. ‘I see he didn’t bother to sign it. Anything on the envelope?’

‘Nothing helpful.’ He sat back in the chair. For more than two years this had been his office, but Kendall’s ghost still seemed to linger; sometimes he even believed he could smell the shag tobacco the man used to stuff in his pipe. ‘All the women candidates running to be on the Board of Guardians received one.’

‘I see. That was Mrs. Harper’s, I take it?’

‘There was another yesterday. She burned it.’

‘Whoever wrote this was educated,’ Fowler said. ‘All the lines are even, everything spelled properly.’ He grinned. ‘Of course, that’s doesn’t mean he’s not barmy.’

He pushed the spectacles back up his nose. The sergeant had been recommended by a copper from Wakefield. He was moving back to Leeds to be closer to his ill mother. Harper had taken a chance on the man. Over the last twelve months it had paid off handsomely.

Fowler didn’t look like a policeman, more like a distracted clerk or a young professor. Twenty-five, hair already receding, he barely made the height requirement and couldn’t have weighed more than eleven stone. But he had one of the quickest minds Harper had ever met. He and Ash had clicked immediately, turning into a very fruitful partnership. One big, one smaller, they seemed to work intuitively together, knowing what each one would do without needing to speak.

‘This woman’s had another letter, too.’ He gave them the address. ‘Go and see her. I doubt we’ll track down the sender, but at least we can put out the word that we’re looking into it. That might scare him off.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Ash stood. ‘How’s Mrs. Harper’s campaign going?’

‘Early days yet.’

She’d only held small one meeting so far, in a church hall just up Roundhay Road from the Victoria. Their bedroom was filled with piles of leaflets read to be delivered and posters to plastered on the walls all over Sheepscar Ward.

‘I’m sure she’ll win, sir.’

He smiled. ‘From your lips to God’s ears.’

Once they’d gone he turned back to the rota for October, trying to recall when he’d once believed that coppering meant solving crimes.

Billy Reed drew back the curtains, pushed up the window sash, and breathed in the sharp salt air. After so many years of soot and dirt in Leeds, every day of this seemed like a tonic. He heard Elizabeth moving around downstairs, cooking his breakfast.

They’d been in Whitby since July, all settled now into the terraced house on Silver Street. The pair of them, and her two youngest children, Edward and Victoria. The older ones had stayed in Leeds, both in lodgings, with work, friends, and lives of their own.

Moving had been a big decision, an upheaval. He’d come to love Whitby on his first visit. He’d left the army, just home from the wars in Afghanistan and troubled in his mind. The water, the beach, the quiet of the place had brought him some peace, and he’d always wanted to live there. But when he’d seen the job for inspector of police and fire in the town, he’d hesitated.

‘Why not write?’ Elizabeth urged him. ‘The worst they can say is no.’

‘We’re settled. I’m doing well the with fire brigade. And you have the bakeries.’

She stared at him. ‘Do you think we’d be happy there?’

‘Yes,’ Reed answered after a moment. ‘I do.’

‘Then sit down and write to them.’

It had taken time. First the application, then an interview, Elizabeth travelling with him on the train and inspecting the town while he was questioned by the watch committee. Another wait until the answer arrived, offering him the position. After that, it was a scramble of arrangements. In the end he’d gone on ahead while she finished up the up sale of the bakeries, packed the rest of their possessions, and said goodbye to all the friends they’d made.

He had no regrets. He liked his job, but it was time for a move, for something new. And this was certainly different. He could make out the shouts of the fishermen at mooring points as they unloaded their boats, and hear the gulls calling.

‘You’d better come and get it while it’s hot,’ Elizabeth shouted up the stairs.

The children were already eating, ready to scramble off to their jobs. Soon enough, Elizabeth would march down Flowergate, across the bridge, and along Church Street to the shop she’d leased, ready to open her tea room and confectioner’s in the spring. She’d made the bakeries in Leeds turn a fair profit, and she wasn’t one to be content as a lady of leisure. She relished work.

‘It’s right by the market,’ she pointed out to him. ‘And all those folk going to the abbey in holiday season will pass by the door.’

She’d developed a good eye, he knew that, and she’d already managed to cultivate a few friends in town, like Mrs. Botham, who ran her bakery and the Inglenook Tea Room on Skinner Street. A formidable woman, Reed thought, but she and Elizabeth could natter on for hours.

He’d quickly settled into the rhythm of his job. During the summer it was mostly dealing with complaints from holidaymakers and breaking up fights once the pub closed. There had only been one fire, and that was easily doused.

He strolled over to the police station on Spring Hill and went through the log with the uniformed sergeant before setting off in the pony and trap. Sandsend and Staithes today. Both of them poor fishing villages, and little trouble to the law, but he still needed to put in a monthly appearance. Show the flag. He covered a large area, going all the way down to Robin Hood’s Bay, but on a day like this, with the sun shining and a gentle breeze blowing off the water, nothing could be a better job.

No, Reed thought with a smile as the horse clopped along the road, no regrets at all.

Two

‘I saw Mrs. Bolland, sir.’ Ash settled on to the chair in the superintendent’s office. ‘She’d kept the letter.’ He ran his tongue round the inside of his mouth. ‘It left her scared.’

‘What does it say?’ Harper put down the pen and sat back.

‘Read it for yourself, sir.’ The inspector pulled a folded sheet of notepaper from his inside pocket.

A woman’s place is in the home, tending to her family and being a graceful loving presence. It’s not to shriek in the hustings like a harridan or to display herself in front of the public like a painted whore.

The Good Lord created His order for a purpose. Man has the reason, the wisdom, and the judgement. He’s intended to use it, to exercise his will over women, not to be challenged by them, the weaker element. Eve was persuaded to eat the apple and tempted Adam, and since that time it has been her duty to pay for the sin.

It is time for you to withdraw your candidacy. Should you fail to do so, if you continue to talk and challenge men for what rightly belongs to them, we shall feel justified in taking whatever means necessary to silence you for breaking God’s profound will.

‘A death threat. No wonder it frightened her.’

‘Yes, sir. Funny what these types come up with in the name of religion, isn’t it? It was all love thy neighbour when I was at Sunday school.’ Ash gave a wry smile.

Harper took out the first letter from his drawer and compared them.

‘The same handwriting. Twice means he’s more than a crank. We’re going to follow up on this and make sure nothing happens to her.’ He thought about Annabelle. ‘To any of the women. Where’s Fowler?’

‘I sent him off to talk to the others, to see if they’d had anything like this.’

‘Odds are that they have. That “we” in there makes me wonder, too.’

‘I noticed that, sir.’ Ash pursed his lips. ‘If I had to guess, thought, I’d say it’s a man on his own.’

‘I agree. Still…’

‘Better safe than sorry, sir.’

‘Exactly.’ He wondered why his wife had destroyed the letter. Not to keep it away from Mary; she could manage that by hiding it in a drawer or on the mantelpiece. Had it terrified her? She was so strong that it seemed hard to believe. But this election campaign was already putting a strain on her and it had hardly begun. ‘No signature again. Handy, isn’t it? He can just pop it in the post, then sit back and stay anonymous behind the paper.’

‘Any ideas for catching him, sir?’

‘No,’ Harper said with a sigh. ‘We’ll just stay on our guard.’

‘How was your dinner last night, by the way, sir?’ The inspector smiled slyly. ‘Big do, from all I hear.’

‘Big?’ Harper asked. ‘Pointless, more like. Tasteless food that was barely warm by the time it reached the table, followed by an hour of mumbled speeches.’

‘The perks of rank, eh, sir?’ Ash’s eyes twinkled with amusement.

‘You’d better be careful, or I’ll start sending you in my place.’

‘My Nancy would probably enjoy that.’ He grinned, slapped his hands down on his knees and stood. ‘I’ll go out and ask a few questions. Who knows, maybe we’ll be lucky and our gentleman writer isn’t as discreet as he should be.’

‘If you really believe that, I’ll look out of the window for a herd of pigs flying over the market,’ Harper told him.

‘Stranger things have probably happened, sir.’

‘Not in Leeds, they haven’t.’

‘Was your letter like this?’ he asked. Mary was tucked up in bed, exhausted by a day of school and an evening of telling them every scrap of learning that had gone into her head since morning. Harper was weary from concentrating, trying to make out all the words with his poor hearing.

Annabelle read it. ‘Word for word,’ she said, quickly folded it and handed it back to him.

‘Ash and Fowler are after him.’

‘Doesn’t help if you don’t know who you’re chasing,’ she said. They were in the bedroom. He sat by the dressing table while she counted election leaflets into rough bundles, ready to be delivered tomorrow. She raised her head. ‘I’m not a fool, Tom. There’s not enough in that for you to find him.’

‘We can ask around. And I’ll make sure there’s a copper at the meetings.’

Annabelle stopped her work and stared at him. ‘Would you do that for the men?’

‘Yes,’ he told her. ‘If I believed things could get rowdy,’

‘Don’t you think it’s wrong that women should need special protection? We’re in England, for God’s sake.’

‘Of course it’s wrong. But when there are men like this poison pen writer, it’s better than something bad happening.’ He let the idea hang in the air. ‘To any of you.’

Her stare gradually softened to a curling, twinkling smile.

‘Well, if you really want to look after me, Superintendent, perhaps you could offer me some very close guarding of my body.’

He grinned and bowed. ‘My pleasure, madam.’

‘They all received identical letters,’ Fowler said. He pushed the glasses back up his nose and produced the papers from his pocket. ‘Three had burned them. But it’s the same wording and the same handwriting as Mrs. Bolland’s.’

‘And the one my wife received,’ Harper confirmed. ‘What do you two have on your plates are the moment?’ he asked Ash.

‘Next to nothing, sir. We’ve been too successful, that’s the problem.’ He smiled. ‘They’re all too scared to commit crimes these days.’

‘Better not get over-confident,’ the superintendent warned. ‘We might be up to our ears tomorrow. While you have the chance, spend some time with this. Do you have a list of where and when these women are holding meetings?’

‘I do,’ Fowler said. ‘There are four tonight.’

‘Make sure there’s a uniform at every one of them. And I want him very visible.’

That should deter any trouble, he thought. If it didn’t, the weeks until the election were going to be difficult.

‘Mr. Ash and I have been talking, sir,’ the sergeant began. ‘We thought perhaps we could each go to a meeting. You know, stay quiet and keep an eye out for anything suspicious.’

‘A very good idea. Not my wife’s, though,’ he added. ‘I’ll take care of that.’

He’d grown used to the routine of running a division, of being responsible for everything from men on the beat to the number of pencils in the store cupboard. But it still chafed. So much of the work was empty details and routine; a competent clerk could have managed it in a couple of hours.

Meetings were the worst times; every month, all the division heads with the chief constable. So far they’d never managed to resolve a single thing. Then there was the annual questioning by the Watch Committee, the council members who oversaw the force. Several of them had no love for him, but he’d managed to fox them. The crime figures kept falling, and he stayed well within his budget. He hadn’t walked away with their praise, but he’d been pleased to see that his success galled them.

Small, worthless victories. Had he really been reduced to that? Sometimes two or three days passed with him barely leaving Millgarth. It felt as if an age had gone by since he’d been a real detective. It was one reason he was looking forward to tonight. Standing at the back of the hall, watching the faces and the bodies, thinking, alert for any danger. At least he could feel like he was doing some real work. That made him smile.

One the stroke of five, Harper pulled on his mackintosh and hat and glanced out of the window. Blue skies, a few high clouds, and a lemon sun; a perfect autumn afternoon. Saturday, and a little time away from this place. Not free, though: he’d spend it walking round Sheepscar, delivering leaflets for Annabelle’s campaign.

Ash was at his desk in the detectives’ office, writing up a report.

‘Did you find anything?’

‘Not a dicky bird, sir.’ He sighed and scratched his chin. ‘You weren’t banking on it, were you?’

‘No.’ He shook his head. ‘If there’s anything tonight, make sure you let me know.’

‘I will, sir. Let’s hope it’s peaceful, eh?’

It was warm enough to walk back out to the Victoria. Even if the air was filled with all the soot and smoke of industry, so strong he could taste it on his tongue, it still felt good to breathe deep after a day in a stuffy office.

‘Do you think I look all right, Tom?’ Annabelle stood in front of the mirror. She was wearing a plain dress of dark blue wool. It was cut high, at the base of her throat, modest and serious. Her hair was up in some style he couldn’t name but had probably taken an hour to engineer so it looked nonchalant.

‘I think you look grand,’ he told her. ‘Like a member of the Poor Law Board.’ He nudged Mary, who was sitting on his lap, staring in awe at her mother.

‘Da’s right. You’re a bobby dazzler, mam,’ she said. ‘I’d vote for you if I could vote.’

‘That’ll do for me.’ Annabelle picked up her daughter and twirled in the air. ‘You’re absolutely sure?’

‘Positive,’ Harper replied. He pulled the watch from his waistcoat. ‘We’d better get going. That meeting starts in three-quarters of an hour.’ It wasn’t that far – the hall at the St. Clement’s just up Chapeltown Road– but he knew she’d want to arrive early, prepare herself, and put leaflets on all the chairs. Ellen would bring Mary shortly before the meeting started.

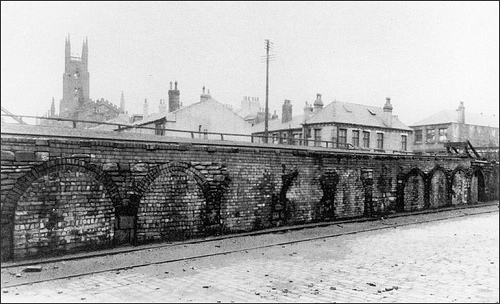

It was a fine evening for a stroll, still some sun and a note of warmth in the air. The factories had shut down until Monday morning, the constant hums and drones and bangs of the machinery all silenced. The chimneystacks stood like a forest, stretching off to the horizon, their dirt making its mark on every surface around Leeds.

Annabelle took his arm as they walked. He’d put on his best suit, the dove-grey one she’d had Moses Cohen tailor for him seven years before. It was still smart, but growing uncomfortably tight around the waist.

‘It’s going to be fine, isn’t it?’ she asked.

‘Of course it is.’ He glanced over at her. ‘It’s not like you to be so nervous. You usually dive right in.’

‘This is something new, that’s all. And if I fail, well, it’ll be obvious, won’t it? I’d be letting everyone down who’s helping.’ She nodded at the hall, just visible beyond the church, its low outline stark against the gasometers. ‘All of them who turn up tonight. If anyone does.’

‘You’ll be fine.’ He kissed her cheek. ‘That meeting two nights ago was packed.’ He grinned. ‘Trust me, I’m a policeman.’

‘I thought you lot were only good for telling the time.’

The words had hardly left her mouth when he heard the low roar. It grew louder, then a deep violent explosion ripped out of the ground. A column of smoke plumed up from the hall, throwing wood and roof and bricks high into the air.

‘Christ.’ They stared for a second, not knowing what to say. It was beyond words. ‘Stay here,’ he told her, then changed his mind. ‘No. Go home.’

Tom Harper was running towards the blast.