Leeds, Summer 1898

No rest for the wicked, Annabelle Harper thought as she picked up the post. A card on top with a view of Masham. Jotted on the back: Staying here tonight. There’s a brewery, it smells like when I worked at Brunswick’s! Beautiful weather, we’ll come home brown as berries. Love, Tom. And underneath, in a careful hand: And Mary.

She smiled and placed it on the mantlepiece with the other two. One a day, exactly as he’d promised. High summer, 1898, and her husband had taken their daughter on holiday to the Dales. He had a week’s leave, school had finished. But no chance for a Poor Law Guardian to take a little time away.

Three people had needed assistance yesterday, two the day before, five on Monday. That was always the worst day. Wages spent, everything worth even a couple of pennies hauled off to the pawnshop. Some she’d been able to help. Others she’d had to turn away, hurting at the hopelessness on their faces. Things were always bad in Sheepscar. Worse in other parts of Leeds, she knew that. But a year of this work had shown her that not everything was possible. She’d learned to steel her heart; sometimes she had no choice.

But she was the won who’d wanted to run for the position. She’d won the vote, and now she had to do the job. A pile of papers sat on the table needing her attention. Reports from the workhouse, minutes from the last Guardians meeting. And barely a minute to read them. She glanced at the clock, then strode over to the mirror, pinning her hat in place before she wrapped a light shawl around her shoulders.

Downstairs, the bar at the Victoria was quiet. A couple of older men ekeing out the boredom of their days by playing game after game of dominoes and cribbage while they sipped at halves of mild. A quick word with Dan the barman, a pull of the door and she came out into the clatter and din of Roundhay Road. Already warm, the sky hazy, the streets heavy with soot and dust and all the stink of industry.

Annabelle had barely started walking when a man called her name. She turned, seeing Reverend Fletcher hurrying to catch up to her. He looked like a figure of fun, a large man with a red, florid face above the dog collar and a belly that wobbled as he tried to move quickly. But he was a good soul, doing what he could to help the poor in his parish. She couldn’t help but have a soft spot for him.

‘Mrs. Harper. I’m glad I caught you.’ Just ten yards and he was already out of breath, she thought. He lifted his straw hat and panted.

‘Pleased to see you, too, Reverend. If there’s something you need, you’d better walk with me, I’m already late.’ She nodded towards the distance. ‘I’m due at the workhouse in a quarter of an hour.’

‘Of course.’

She kept a brisk pace, nodding at shopkeepers and folk she saw on the way to the junction with Enfield Street. He had to move quickly to keep pace.

‘There’s someone I’d like you to see, if you’d be so good,’ Fletcher said.

‘One of your flock? Is the family having money problems? Out of work?’

He hesitated before answering, just long enough to make her turn her head and stare.

‘No, it’s nothing like that. He’s only been in Leeds for a few weeks now, still has a pound to his name.’

She stopped, hands on her hips.

‘I don’t understand, then. What do you need with a Guardian?’

‘He’s staying at the Vicarage. With his wife and children.’ A shy smile crossed Fletcher’s face. ‘If you could call around later. Just for a minute or two. I’d be very grateful.’

Annabelle narrowed her eyes. ‘You’re being very cagey. What’s it all about?’

Fletched tightened his mouth, then shook his head. ‘I’d rather you made up your own mind. Shall we say this afternoon?’ He raised his hat again, turned and strode away.

Always someone, she thought as the made her way through the back streets and up the hill to the workhouse.

By the time she walked back out into the air, she was fuming. The same thing as ever: the sheer ignorance of the male Guardians. No clue what women needed when they had their monthlies. Half of them probably didn’t even know such a thing existed; if they ever found out, they’d be terrified.

She breathed deeply, standing until she could feel the pounding in her chest slow down, then crossed the street to Beckett Street Cemetery. The only piece of green around here. A moment or two by Tom Maguire’s headstone, thinking of the man, wondering what he’d make of her now. Then to a bench that nestled in a spot of sunlight.

A few minutes and she was composed again, all the anger tamped down for another few days. Until the next time she visited.

Annabelle stood, dusted off her gown and started to walk home. A quick stop at a bakery for a tongue sandwich and a fancy to go with her tea later. It was only as she strolled down Rosebud Walk, brown paper bags in hand, that she remembered she’d agreed to go and see Reverend Fletcher’s visitor. Pushed into it, more like.

Well, that was the afternoon going through the pub accounts up the spout.

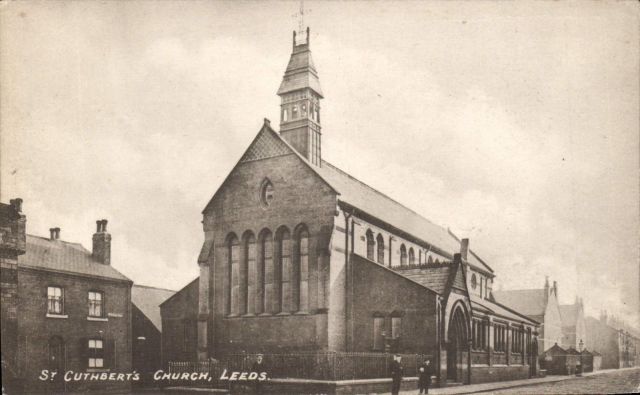

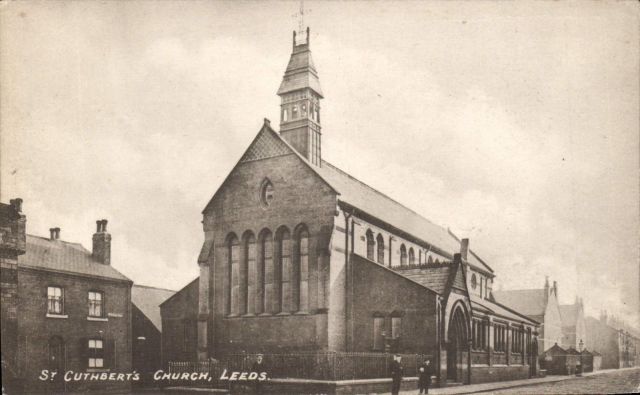

St. Cuthbert’s sat in the sun. The hall had been rebuilt after last year’s bomb. She only had to look at it to remember the noise that filled her head that evening, all the smoke, the stink of gunpowder, and the broken body of Mr. Harkness, the caretaker.

Annabelle straightened her shoulders, trying to put the past to the back of her mind, and brought her hand down on the knocker of the vicarage.

‘Hello, Mrs. Harper, luv,’ the housekeeper said with a warm smile. ‘He said you might be dropping in. Always a pleasure to see you.’

‘He asked me to come and meet your guest.’

‘Yes.’ The woman’s face clouded. ‘Well…’

‘A strange one?’ Annabelle asked.

‘You could say that.’ She frowned as stood aside, wiping her hands on her apron. ‘Come on through, luv. He’s in the back parlour.’

‘What about his wife and children?’

‘Child,’ the woman corrected her. ‘They’re out,’ she said darkly.

Annabelle blinked in the bright sunlight and started to walk down the street. She stopped, half-turned, then carried on towards home.

Well, she’d certainly never met anyone like that. Even when she was sitting upstairs at the Victoria with a cup of tea, she still didn’t have a clue what to make of him. Who on earth would walk all the way from London because God had told him to bring the light to the people of Leeds? If he’d come alone it would be bad enough, but to drag a wife and two-year-old boy with him…

His name was Harry Walton. He was small, shifty, not much to him, probably no taller than five feet three, skin and bone from weeks on the tramp. But there was an intensity to his eyes that worried her. In his voice, too. He spoke with the kind of certainty she’d heard before in con men with something to sell. But he didn’t seem to want anything.

‘Leeds is the holy city. The Lord told me that.’ He stared straight at her as her spoke, unblinking behind his spectacles.

‘The holy city?’ Annabelle asked. ‘What’s that supposed to mean? I’ve lived here all my life. Take it from me, there’s nothing holy about it.’

‘The people here will be saved if they rid themselves of evil. God told me. That’s why He sent me here, to reform them.’

Round and round for more than half an hour, until she felt overwhelmed, her head spinning.

‘What about your family?’ she asked finally.

‘They go where I go.’ He spoke the words with absolute finality, as if they’d been ordained. Maybe he believed they had.

Time to see about that, Annabelle thought as she finished the cup of tea and carried it through to the kitchen. See what the woman felt about it all. The pastry sat, barely touched on the plate. Too dry, no flake to the crust. If Mary had been here, she’d have wolfed it down. That girl had an appetite like a gannet.

This time the reverend answered the door himself. He looked surprised to see her, recovering his manners after a second.

‘Come in, Mrs. Harper. Come in. Forgive me, the housekeeper told me you were here this afternoon.’

‘I was,’ she answered with a soft smile. ‘I’ve come back to see the man’s wife.’

‘Ah,’ Fletcher said. ‘And what did you make of the gentleman?’

‘Honestly?’ she said. ‘Happen he believes everything he says. But holy city and cleansing the place, reforming it? I think he’s got something up his sleeve that we haven’t seen yet. Either that or he’s a bit touched.’

‘Men of God have often been viewed that way.’

‘Is that what you think he is?’ she asked.

Reverent Fletcher spread his hand, palms upwards.

‘I wish there was a way to know. But he’s right that we need to be rid of sin here, isn’t he?’

‘What? Like drinking?’ She had a twinkle in her eye. He knew exactly what she did for money.

He laughed. ‘Wine is there in the Bible, Mrs. Harper. Jesus even changed water into it at a wedding feast.’

‘He’d be welcome at the Victoria to do that any night he wants, although they’d prefer it was beer,’ she said, and suddenly realised she might have gone too far. ‘No offense, Reverend.’

‘None taken. I’ll have the lady attend you here, if that’s fine.’

‘Perfect.’

One minute stretched to two, then five, before the door opened and the woman entered.

Not a woman, Annabelle thought. A girl. She had to be thirty years younger than the man. Probably not a day over seventeen, looking shy and cowed.

‘Come on in and sit yourself down.’

Stick legs under a thin cotton dress. Boots with worn soles and woollen stockings she’d darned too many times. Hands as rough as sandpaper.

‘I’m Mrs. Harper. The Reverend asked me if I’d have a word with you and your husband.’ Not quite the truth, but close enough. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Julia.’

‘That’s a pretty name. I like that. My mother lumbered me with Annabelle. I’ve always thought it sounds like it should be the name for a flower.’

The girl was too timid to respond.

‘How long have you been married?’

‘Two years,’ Julia answered. ‘Just after Samuel was born. He’s my son.’ She had the same rounded London vowels as her husband, so strange and out of place. But there was nothing educated about either of them.

‘The reverend said you had a child. A bonny little lad, I bet.’

‘He is.’ Her face came alive. ‘He takes so much time. And he’s always so hungry.’

Annabelle smiled. ‘It doesn’t get any better. My daughter’s six and she has hollow legs.’ She paused for a second. ‘Do you mind if I ask your age, Julia?’

A small hesitation. ‘I’m nineteen.’

That was a lie, Annabelle thought, but she’d let it pass.

‘How do you like being on the tramp?’

‘I don’t.’ Her mouth turned down at the corners. ‘My feet hurt all the time. This is the best place we’ve been since we left London. But I know we’re going to have to find somewhere else soon.’

‘I came and talked to your husband this afternoon, but you and your lad were out. Taking a look around?’

The girl shook her head. ‘Harry sends us out to beg. He says a woman and child bring in more than a man.’

Well, she though, he might have his eyes set on a holy city, but he kept a thought for bringing in the brass.

‘Do you make much?’

‘No,’ she answered. ‘Most of the time a rozzer will come and move us on. I was arrested once, when we were in Birmingham.’ Her face fell at the memory. ‘Seven days of hard labour and they almost took Samuel away from me.’

‘You must love your husband to do all this.’

‘He says it’s a wife’s duty to obey. A woman has to follow a man’s desires.’ She sounded as if she was repeating words she’d heard far too often.

‘How did you end up marrying him? There’s…’

‘I know. He’s a lot older.’ The deadness came back to her. She looked around, as if someone else might have come in and be hiding in the corner, listening. ‘Harry used to play cards with my pa. They worked together.’ Annabelle felt the first prickle up her spine, the sense that she knew exactly what was coming. ‘My pa had a losing night, so he told Harry he could have a poke of me and they’d all be square.’

‘How old were you?’

‘Fourteen.’

‘What about your mam? Where was she?’

‘She left when I was ten,’ Julia said. Her shoulders slumped. ‘Everything was good when she was still there.’

‘You and Harry…’ Annabelle said.

‘He got me…’ She blushed and lowered her gaze. ‘My pa told him he had to marry me to make it right. And pay a him a…something, I don’t remember what.’

‘A dowry?’

‘Yes. I think that was it.’

Annabelle sat quietly, thinking, then asked: ‘Tell me something, luv. Are you happy with Harry?’

‘Happy?’ Julia said, as if she’d never heard the word before, never considered the idea.

‘Do you love him?’

She shook her head, moving it quickly from side to side like a little girl.

‘Not like I loved my mother.’ She leaned forward and her voice softened to a whisper. ‘He hurts me when we…you know… and he hits me if I do something he doesn’t like.’

So much for any kind of holy man. Had his feet near the devil, like so many of them.

‘What do you want? For you and little Samuel?’

‘Want?’ She frowned, confused. ‘I don’t know. No one’s ever asked me that before.’ A moment passed, then she started to answer, voice like a child wishing for the Christmas presents that would never arrive: ‘A place we didn’t have to leave. Enough to eat. Not to ache from walking all the time. Things to make Sammy smile.’

Hardly reaching for the moon. Things any mother wanted. Yet Annabelle knew half the women she saw every week didn’t have them. They turned up to see her, clutching their sorrows close, hiding the bruises they claimed came from walking into doors and filled with the same of asking for something.

Annabelle knew how she must appear to the girl. A grand lady in an elaborate frock and big hat. A Poor Law Guardian with all sorts of power. But Julia was a stranger here, lost in an unfamiliar place. A stranger in her own life, really. She’d never had a chance to grow up the way a child should.

‘Have you ever worked before? What can do you?’

‘I was in a match factory for two years. But it was making me ill so I had to stop. I kept being sick. My pa belted me for that. He didn’t see the use of me if I couldn’t bring in money.’

‘Anything else?’

She blushed hard and stared down at her feet again.

‘Harry had me on the game for a little while. I had to stop when I started to…’ She curved a hand around her belly.

‘I want to ask you something.’

‘You’ve already been asking me things, missus.’

‘I know, but this is…well,’ Annabelle smiled and softened her voice. ‘It won’t go past these four walls, word of honour. If you had your druthers, would you stay with him?’

The girl looked up, pain showing in her eyes.

‘What else could I do? There isn’t anywhere me and Sammy could go.’

‘If someone could find a place. Somewhere safe. Would you stay with him then?’

Julia didn’t hesitate. ‘No. But I can’t go back to my pa. I won’t do that.’

Of course not; he’d beat her and sell her all over again.

‘I know. Look, I can’t make you any promises, but let me see what I can do.’ She took out her purse and counted out three pennies. ‘You buy your little lad something with that. And don’t let your husband know you have it.’

‘I won’t, missus. I swear.’ She clutched the coins in her fist as if they were the most precious gift she’d ever been given. ‘Thank you.’

‘I’ll come and see you tomorrow.’

Reverend Fletcher closed the front door behind them, staring across at the church.

‘All this talk about the holy city,’ Annabelle began. ‘It’s a con. He’s no more got religion that I have.’

‘But…he sounds so sincere.’

‘That’s his game. Do you want to know the truth. He won that lass from her father in a card game, he’s had her out on the streets.’ She saw him wince. ‘He’s happy to have her and their lad out begging to support him. Does that sound like a man of God to you?’

‘No,’ Fletcher admitted. ‘I suppose I’m gullible. He must have seen it. But what do you want me to do? Throw them all out on the streets?’

‘Give me a day,’ she said. ‘I’ll see what I can come up with for her and the boy. But I’ll tell you this – I won’t lift a finger to help him. If I were you, once they’re gone, I’d toss him out on his ear. Let him find a proper job.’ Her face turned grim. ‘If he doesn’t, I’ll have one of Tom’s men run him in for vagrancy.’

An evening of bustling around, feeling like she was shuttling from pillar to post and back again. The books would have to wait for another day.

She didn’t sleep well, thrashing around and throwing the covers off in the summer heat. The bed felt too big without Tom here, and the morning was empty of all the bustle of her husband and Mary. Cooking breakfast just for herself seemed like a chore. It left her lonely. She rushed through it, washed the pots and was out of the door by seven. Another postcard from Middleham waiting on the mat. Home on Sunday written on the back. Not long now, she though as she put it in her reticule.

The problem was finding a place for the girl and her son to live, and someone to look after the boy. There were jobs out there, maybe nothing much, but enough to keep body and soul together.

By dinnertime she’d talked herself hoarse, wheedled, pulled in favours from people she’d helped in the past. Finally she secured the offer of a room for Julia Walton and her son. Just for a month, but the woman in the house was willing to look after Samuel. That would give her the breathing space to find a job and come up with somewhere else to live.

Annabelle paid the month’s lodging. It seemed only fair. She was the one encouraging the girl to leave her husband; this might be enough to help her take that step. All too often she’d seen the way women with no money were too scared to go. God knew she couldn’t help them all, but even one…it was a start. Didn’t matter that she wasn’t from round here. Perhaps it was more important because she was a stranger in Leeds, with no family or friends to turn to. Being alone brought desperation.

One final stop. The tram down to Millgarth police station, a few words and a laugh with Sergeant Tollman on the desk, then through to see Inspector Ash. It seemed strange to see someone else behind her husband’s desk, as if he might never return, instead of due back in a couple of days. He rose, looking confused, as she entered the office.

‘Has something happened to the Superintendent?’

She ginned. ‘Don’t worry. You’re not likely to be stuck there past this week. I’ve come to ask a favour. Can you check the past of someone I met? He’s come from London…’

Home. She treated herself to a cup of tea and settled in the chair, unbuttoning her boots and wiggling her feet. Absolute. Just having the chance to sit, a few minutes to herself, seemed like luxury after all the rushing about.

Then the knock on the door, and a young bobby who’d hardly started to shave was standing there.

‘Inspector Ash asked me to bring you this and wait for a reply.’

‘Come in,’ Annabelle told him. ‘There’s still some left in the pot.’ He waited, shifting nervously from foot to foot, not daring to pour himself a cup of tea. ‘Don’t worry, I won’t tell anyone.’

She unfolded the note. Ash’s copperplate was a joy to read, so much better than her own scrawl.

Harry Walton has a record as long as your arm. Currently wanted in London for passing altered cheques. They asked if we could arrest him. Do you know where he is?

No wonder he’d wanted to vanish. She sat at the table, a piece of paper in front of her, and dipped her nib in the inkwell.

St. Cuthbert’s. Best if it’s first thing tomorrow morning. He’d find out just how holy this city could be.

‘Give that to him with my thanks, will you?’

‘Yes, missus,’ the lad said, blushing as he corrected himself. ‘Mrs. Harper.’

The same room, the woman in the same thin, faded dress. The only difference was the boy sitting on the floor, spinning the reverend’s globe again and again, mesmerised by it.

‘That’s it,’ Annabelle said as she finished. ‘It’s yours if you want it.’

‘I don’t know what to say,’ Julia told her.

‘You don’t have to say a word. Just put your things in a bag and come with me.’

‘Why, though?’ She stared at Annabelle with suspicion. ‘Why me? Us.’

‘Because you need it. I know, there are plenty who do. All I did was talk to a few folk. It wasn’t much.’ She stood and held out her hand. ‘Ready?’

‘What about Harry?’

‘Believe me, you won’t need to worry about him.’

As the vicarage door closed behind them, the light was starting to drift from afternoon into evening.

‘I’m scared,’ Julia said. Samuel marched beside her, clutching tight to her fingers. ‘I’ve never had to look after myself before.’

‘Seems to me you’ve been doing that for most of your life,’ Annabelle told her. She looked down at the boy and stuck out her tongue until he giggled. ‘This time will be better.’

I hope you liked it. This story takes place the summer after the vents in The Tin God, and a year before The Leaden Heart (out next March).

Remember, books make great gifts, and I’ve had three out this year – The Tin God, The Dead on Leave, and The Hanging Psalm.